13/01/2014

The legislation setting up the process for filing a single European patent application was agreed forty years ago in 1973 with the first European patent applications being filed five years later in 1978. The number of European patent applications per year has grown over that time from 4000 to over 265,000 (from figures released this week). The number of European states within the European patent system has also increased from the seven founder members to the current 38 states including all 28 European Union countries, most of the Balkan states and Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and Turkey. In 2012, 63% of European patent applications were filed by non-European companies with the US topping the league table at 25%, followed by Japan (20%), China (7%) and Republic of Korea (6%) (figures for 2013 not yet available but broadly expected to follow 2012 figures).

But grant of a European patent application is not the end of the current European patent process. The granted European patent must be validated in each individual European contracting state in which it is to take effect and any disputes arising from the validated granted patent take place in that particular state.

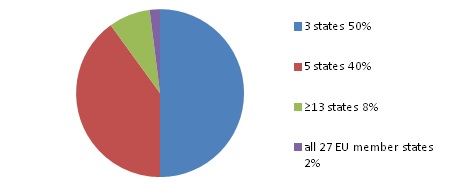

Around 50% of European patents are validated in three states, with five state validation still very common at around 40%.

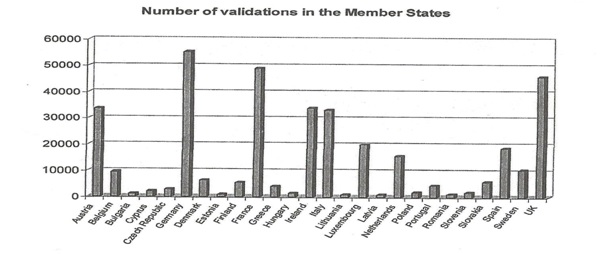

Unlike the United States of America, the European contracting states do not share a common official language. Validation requirements differ between European contracting states and include validation fees and translation requirements. The validation costs and the cost of yearly renewal fees in each state mean that most applicants face a tough decision of how best to maximise patent protection across Europe whilst balancing their patenting budget. The overall effect is a marked imbalance between rates of validation across the European contracting states as shown in the graph below1.

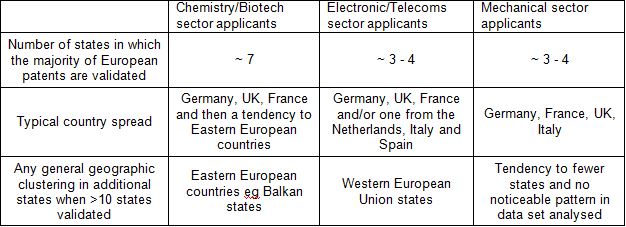

What the figure does not show is whether there is any difference in validation strategy, in terms of numbers of validation states and the geography of validation states, across different industry sector groups. The table (generated by analysing a limited data set) adds a perspective on that missing picture and suggests that there are differences in the behaviour of applicants of different industry sectors.

The unitary patent is intended to change the patent landscape in Europe by creating a single European patent covering the European Union (EU) member states. However, not all EU member states are convinced by the new system. Italy, Spain and Poland are unlikely to be part of the Unitary Patent system and it is not yet clear whether Croatia, which joined the European Union in July 2013, will sign up to the Unitary Patent system or not.

In our recent talks on the Unitary Patent and Unified Patent Court we discussed that with around a 2% European patent validation rate, suitable labour market and central European location, Poland might be seen as an attractive base to manufacturers keen to avoid patent infringement. This could be a major factor in their decision not to sign up to the Unified Patent Court and thereby remain outside the Unitary Patent system.

From a European perspective, the change to a Unitary Patent covering 24 or 25 of the 28 EU member states will fundamentally alter the face of European patenting. The Unitary Patent system will require a lot of adjustment to shift from a mindset of distinct patent coverage within separate European states, albeit within a common economic area, to a large pan-European single patent arena. It remains to be seen whether there will be a difference in uptake of the unitary patent across different technology sectors but the tendency to validate in more countries shown by European patents in the chemistry/biotechnology sector might suggest higher uptake in this sector. However, there are many other important factors which will come into play in the decision and we shall have to wait for a number of years after the unitary patent comes into effect to assess such trends. For practitioners and applicants outside the European patent contracting states, I suspect the move to a Unitary Patent system will seem long overdue. The coverage2 of the Unitary Patent system will, I suspect, continue to perplex even those within Europe.

- Figure 7 of Commission Staff Working Paper SEC(2011) 482 final “Impact Assessment – implementing enhanced cooperation in the area of the creation of unitary patent protection”.

- Not all European countries are members of the European Union. Not all member states of the EPO are members of the European Unions.The Unitary Patent System is currently expected to cover: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, the United Kingdom.Poland, Spain and Italy (whilst EU members) are unlikely to be part of the Unitary Patent System. The Croatian position (EU member since July 2013) is not yet clear.

Albania, Switzerland, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Macedonia, Norway, San Marino and Turkey are members of the EPO but are not in the EU.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking before any action in reliance on it.