11/02/2016

When granted, your patent will prevent your competitors from benefiting from your invention. So, having done your best to describe your technology to your patent attorney, why do you find him or her working and re-working your description and obscuring it with odd words inappropriately conjoined into incomprehensible numbered sentences? Why can’t a patent attorney just describe what you want to sell? A broad and elegantly worded claim 1, followed by a series of intelligently devised and economically advantageous fall-back positions is (in the mind of your attorney) as beautiful a work of art as any of Shakespeare’s history plays. However, this is more than mere artistry: careful drafting is essential to make sure that your patent application is not rejected for claiming too broad a monopoly. We shall attempt to explain this in the following fictional dialogue between a fabricated client (Mr. Smith) and an anonymised patent attorney (Dr. Nala Steab).

Mr. Smith: It’s taken me years of research to devise my new chair. The materials, the shape, the colours, the optimum number of cup holders. The problem is, I don’t think that your claim 1 provides me with the right scope of protection. Why can’t you just describe the bloomin’ thing I want to sell?

Dr. Steab: Your chair has five legs, each formed from extruded aluminium alloy, supporting a mahogany frame strung with a wicker seat. The arms of the chair are hollow carbon fibre tubes with internal earthing wires, and the back is mock 18th century fiddleback with onyx finials. And there are seven cup-holders.

Mr. Smith: That’s it. I want the broadest protection possible; why can’t you just say all that?

Dr. Steab: You have to remember that a patent provides an exclusive right Mr. Smith. The claim of a patent or patent application is a verbal ring fence around subject matter that you want to prevent other people from using without your permission.

Mr. Smith: Subject matter?

Dr. Steab: Never mind that. Let me see if I can explain this graphically {scribbles}.

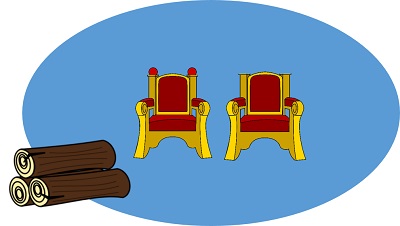

Let’s say that this chair represents your invention…

Mr. Smith: It doesn’t look like my invention.

Dr. Steab: …and I can draft a claim that has all of the features of your invention…{scribbles}…thus.

Mr. Smith: Perfect.

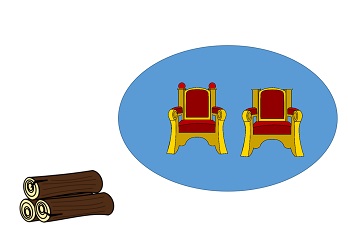

Dr. Steab: Now let’s consider what happens if one of your competitors…

Mr. Smith: Amalgamated Thrones you mean?

Dr. Steab: Could be. Let’s consider what would happen if Amalgamated Thrones produced a chair that was identical to your invention in every respect… except they exclude the finials {scribbles}.

You can only prevent Amalgamated Thrones from making and selling their chair if it has each and every feature that is defined in your claim. As you can see, your claim includes so many features that it only covers a single specific embodiment of your invention. The scope of your claim is not broad enough to cover the modified chair made by your competitor.

Mr. Smith: The swines! How do we stop them?

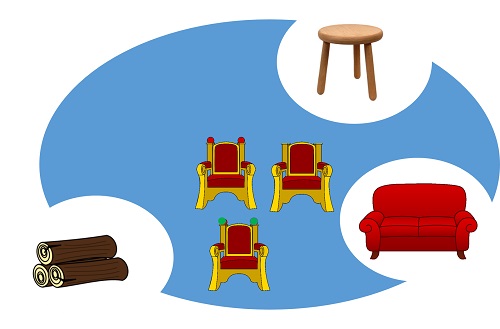

Dr. Steab: Well what we could do {scribbles} is this.

Now we have defined claim 1 as “a seating means suitable for supporting a user above ground level”. Because there are fewer features in the claim, the scope of the claim is broader…

Mr. Smith: … so that we can stop Amalgamated Thrones. Oh that is good news… er… what are you doing?

{scribbling}

Why have you drawn those logs?

Dr. Steab: The problem with broadening the scope of a claim is that you often find it covering things that are already known. We refer to things that are already known as “prior art”. Now in this case, as we can see, the scope of our claim covers a log. A log is prior art and, therefore, the claim lacks novelty. You cannot enforce a claim of this scope because it is not new. But if we add a few more features to your claim… {scribbles} … we can end up with something like this.

Now we have claim with a scope that covers both your product and your competitor’s product but does not cover the prior art. This claim is more likely to be valid and is broad enough to have some commercial value.

Of course the reality is that your competitor may make a chair that has plastic finials instead of onyx finials…

Mr. Smith: I think that is highly unlikely.

Dr. Steab: … and the log is possibly not the only prior art we will come across.

In an ideal world we will have defined your invention with enough fall back positions to enable us to do this {scribbling}.

We have amended the claim to exclude the known prior art while still retaining a broad scope of protection so that we can continue to prevent your competitors from benefiting from your invention.

Mr. Smith: Thank you Dr. Steab. I think I get it now.

Dr. Steab: My pleasure.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.