10/05/2017

Alongside robot uprisings and superintelligent AI, driverless cars have featured regularly in Hollywood’s dramatized portrayal of the future. Notable examples include Will Smith’s Audi RSQ from iRobot, and Tom Cruise’s Lexus 2054, as seen in Minority Report. Both of these films envisage a dystopian future, thanks largely to an overreliance on technologies that, in reality, have not come to fruition. However, it appears that Hollywood could have been on to something with regard to driverless cars. In fact, industry experts believe that fully autonomous vehicles will be commonplace by 2025, with many companies planning to roll out their own vehicles with limited driverless capabilities well in advance of this date.

An industry in gear

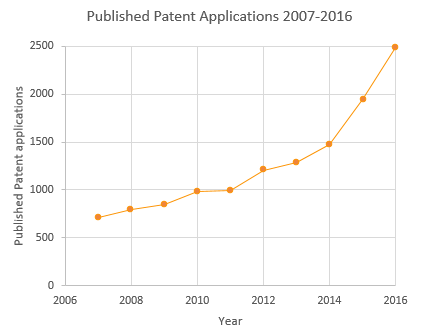

Patent filings are a good indicator of technological growth and innovation in a particular field. With that in mind, we conducted a keyword search of published patent applications mentioning driverless or autonomous vehicles. The number of published patent applications that the search retrieved for the last ten years is given in the graph below.

Although this graph only represents a sample of patent applications for driverless car technology, it clearly shows rapid expansion in recent years. Bearing in mind that patent applications usually take around 18 months to publish from their priority or original filing date, we can expect that many more applications have been filed within the last year and a half.

So what is driving this dramatic growth in patent filings? And what is fuelling the rapid progression of the automotive industry towards full automation?

From a financial standpoint, there has been a lot of investment in research and related technologies in recent years. The UK government pledged £270 million of funding for robots and driverless vehicles in the 2017 Budget, and most recently announced a commitment to spend a further £1 billion in six technology areas, two of which include artificial intelligence and self-driving vehicles.

In the industry itself, there has been a shift towards a more collaborative approach than there has been before. Traditional automotive manufacturers have been investing in technology companies in order to bridge the gap between their hardware and the complex software required to run autonomous vehicles.

In particular, Ford recently announced that it intends to invest $1 billion in Argo AI, an artificial intelligence start-up, over the next five years. Elsewhere, General Motors has bought Cruise Automation, an autonomous vehicle technology specialist. Further companies that have formed partnerships include Volkswagen and Gett, and Volvo and NVidia, for example.

But it is not just the traditional automotive makers that are investing in driverless cars. Indeed, many technology companies have shown their own interest in the field. Google has famously been testing autonomous cars since 2009, accumulating almost 3 million self-driven miles in the process. Apple has recently acquired a licence to test its driverless technology in California, and Samsung has had a self-driving car trial approved in South Korea. IBM, Uber and Intel are also involved with autonomous vehicles.

With so much interest and investment in driverless cars, it is not a surprise that we have seen a dramatic increase in the number of related patent applications. Indeed, the top assignees of these patent applications include many of the companies mentioned previously, as well as Toyota, Hyundai, Bosch, Nissan, Honda and Daimler. Tesla, which already offers an autopilot function, has opened up their patent portfolio as we discussed in one of our previous articles, in an attempt to drive development forward.

Patents for driverless cars

Given the increasing number of patent applications in this area, there are a few patent related factors to keep in mind. For a start, will standards be defined that all driverless cars must adhere to? Will transport infrastructure demand the use of a specific compatible algorithm or piece of hardware? Certainly, a patented invention that becomes part of the standard could be extremely lucrative to the patentee in terms of licensing, as the industry is expected to be worth £900 billion globally by 2025.

Driverless car technology also presents patentability issues, especially with regard to software related inventions. As we have mentioned in previous articles, computer programs must have a technical character, and solve a technical problem, in order to be patentable in the UK and Europe. This means that computer programs that simply automate a process that is already known, or a mental activity, are usually not patentable. How this translates to software in driverless cars is something of a grey area, and is probably more relevant to semi-autonomous vehicles, in which a user may be required to take control and perform an action that provides the technical effect.

Conclusions and further considerations

From the data we have collected and the way the industry has grown, it appears that driverless cars could represent one of the most exciting technological shifts of recent years. Many believe that individual ownership of cars may cease almost entirely by 2025, and be replaced with an automated fleet of safer, more efficient vehicles. Indeed, the positives of driverless cars are clear – fewer traffic accidents, less congestion, and less pollution. Passengers could spend time relaxing, appreciating the surrounding scenery, or maybe even enjoying a few drinks. There are however a few considerations that should be addressed before we hand over the keys to the machines.

A major concern is cyber security. Replacing individual, manually controlled vehicles with a fleet of interconnected machines introduces a vulnerability to large scale hacking. Multiple vehicles could potentially be ordered to shut down, ignore traffic regulations or purposely crash.

Another consideration is the effect of a lack of morality or human instinct. How will a driverless car determine what is the right course of action to take in a morally complex situation? Does the car prioritise the safety of its occupants or the safety of pedestrians?

Recently, a man named Manfred Kick was driving down the Autobahn near Munich when he noticed a car in front of him swerving erratically and hitting the guardrail. Kick realised that the driver of the car was unconscious, and courageously manoeuvred his own car in front to act as a physical brake. Kick effectively allowed the unconscious driver’s car to crash into the back of his own in order to reduce its speed slowly and controllably.

Although a rare occurrence, the actions of Kick most likely saved the other driver’s life. Would a driverless car unnecessarily risk damage to itself in order to do the same?

Such considerations provide scope for further inventions, and we expect that the number of filings of patent applications that relate to driverless technology will continue to increase for the foreseeable future.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.