02/11/2017

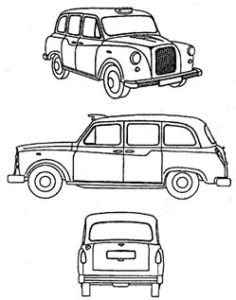

The long-awaited judgment of the Court of Appeal concerning the three-dimensional shape of the London Taxi was handed down yesterday. We discussed the earlier decision of the High Court in January 2016 in which the court said the trade mark registrations depicting the shape of the London Taxi (images below) lacked distinctive character, and would be perceived as “merely a variation of the typical shape of a car”. The registrations were therefore declared invalid. The London Taxi Company (LTC) appealed this decision at the Court of Appeal, raising 26 grounds of appeal. Unfortunately for LTC, whilst they may have succeeded on some of those grounds, they still didn’t get past the key issues of distinctive character, either inherent or acquired through use.

In the earlier decision, the court considered the average consumer of the shape mark(s) as the “average taxi driver”, and not members of the public who hire the taxi for a journey (instead, they were consumers of the taxi services). However, in this latest decision, Lord Justice Floyd saw no reason to exclude the hirer of a taxi (i.e. passenger) from the class of consumers whose perceptions it is necessary to consider, but said in the end, that wouldn’t have any bearing on the outcome of the appeal.

The Court of Appeal stated that the shape of the London Taxi vehicle does not depart significantly from the norms and customs of the sector. In coming to that decision, the court stressed that when deciding what those norms and customs of the sector are, it is necessary to take a step back and look at the sector as a whole, and not merely at one particular design. The relevant sector needs to be viewed with a wider perspective in mind, i.e. consideration to all the different designs of vehicles and the range of variations of each of their features. In doing so, he considered three steps, together with his comments:

- Determine what the sector is

The marks (i.e. the shape of the taxi) were not limited to just London licensed taxi cabs (which, if they had been, would nevertheless include private hire taxis which can be any model of saloon car). The sector includes models in production at the date of application (of the mark), those on the road and those which the public would be expected to have seen.

- Identify common norms and customs, if any, of that sector

Floyd J is of the view that it wasn’t difficult to establish what the norms and customs of the car sector are. Typical cars have a superstructure on four wheels, having a bonnet, headlamps and sidelights or parking lights, a front grille and other features.

- Decide whether the mark (shape of the taxi) departs significantly from these norms and customs

When we compare the London Taxi features with the basic design features of the car sector, each of those features are no more than a variant on the standard design features of a car. None of the London Taxi’s features are so different to anything which had gone before. As a result, they couldn’t be described as departing significantly from the norms and customs of the sector. They were simply minor variants of those norms and sectors.

As to whether the mark(s) had acquired distinctive character through their use, the court says not. The evidence submitted by LTC was unable to persuade Floyd J that consumers would perceive the shape of the taxi as denoting vehicles associated only with LTC and no other manufacturer. Floyd J commented that the public are not used to the shape of a product being used as an indication of origin. In hailing a cab, the consumers’ focus will be on the provider of the taxi services being supplied (i.e. the taxi driver getting them from A-to-B as quickly as possible during rush hour). It won’t necessarily be on the manufacturer or the vehicle in which they are travelling. He remarked that it would be hard to interest them, far less educate them, on the topic of whether the shape of the taxi is an indication of a unique trade source.

This decision is another reminder of the difficulties trade mark applicants and owners face when it comes to the protection of shapes as trade marks. However, if the shape and its particular features do depart significantly from the norms and customs of the sector, it might be enough to satisfy inherent distinctive character. So, does this mean we turn traditionally standard features into something quirkier, or add completely new and unusual features, or both? Trade mark owners also need to make sure that when it comes to their shape mark, they make every effort to educate their consumers that they are the only manufacturer of products of that particular shape. Thinking about LTC’s next steps, seeking permission to appeal to the Supreme Court is expected.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.