15/01/2018

The doctrine of “obvious to try” can be used to assess the inventiveness of a patent claim in the UK. According to this doctrine, a product or process can be inventive even if it is discovered following a series of routine steps. To be inventive, it must not have been obvious to a skilled person to try these particular routine steps, with a reasonable expectation of success, in lieu of any other routes that may have been taken.

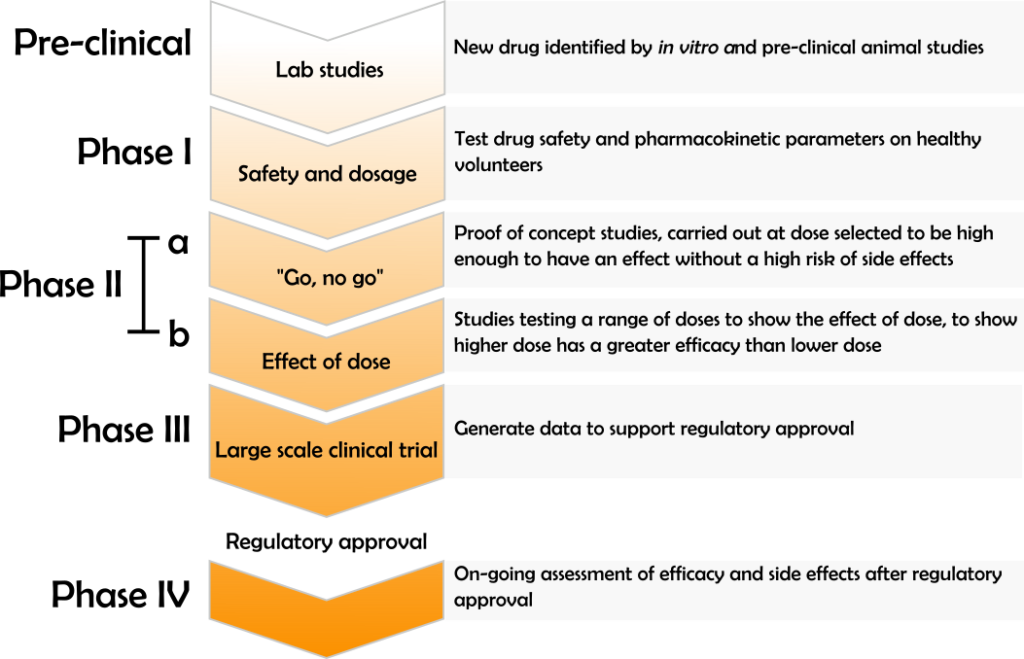

The “obvious to try” doctrine is particularly relevant to the biotechnology and pharmaceutical fields. Many pharmaceutical products arise from systematic and routine investigations, both to discover a drug candidate and to obtain regulatory approval. As summarised below, regulatory approval for a new drug requires clinical data demonstrating the dose range within which a drug is both safe and effective.

The position of the boundary between what doses would and would not have been obvious to try in view of the general schema for clinical trials will impact the inventiveness of any drug or dose regime that receives regulatory approval.

A recent decision by the UK Court of Appeal provided further light on what doses may or may not be obvious to try during clinical trials. Overturning a previous ruling by the UK High Court, the Court of Appeal ruled that patent claims directed towards a particular dose regime would have been obvious to try given the standard procedures followed in clinical trials.

The patent in question related to Tadalafil (CIALIS), an orally administered drug for treating sexual dysfunction. Tadalafil works in a similar way to Pfizer’s famous blockbuster drug VIAGRA, but is said to have fewer side effects. The original Tadalafil patent (EP 0740668, “Daugan”) has expired. The patent at issue in the latest decision (EP 1173181) was owned by ICOS and licensed to Lilly, and related to a dosage regime of Tadalafil.

In an attempt to clear the market for their own Tadalafil generics, Actavis, TEVA and Mylan brought revocation proceedings against the ICOS Lilly patent in the UK High Court, on the grounds that the claims were not novel or inventive in view of the original Tadalafil patent (Daugan). The contentious claims related to a 1-5 mg oral dose of Tadalafil suitable for administration of a maximum total dose of 5 mg per day for the treatment of sexual dysfunction, i.e. a dose regime of up to 5mg Tadalafil per day.

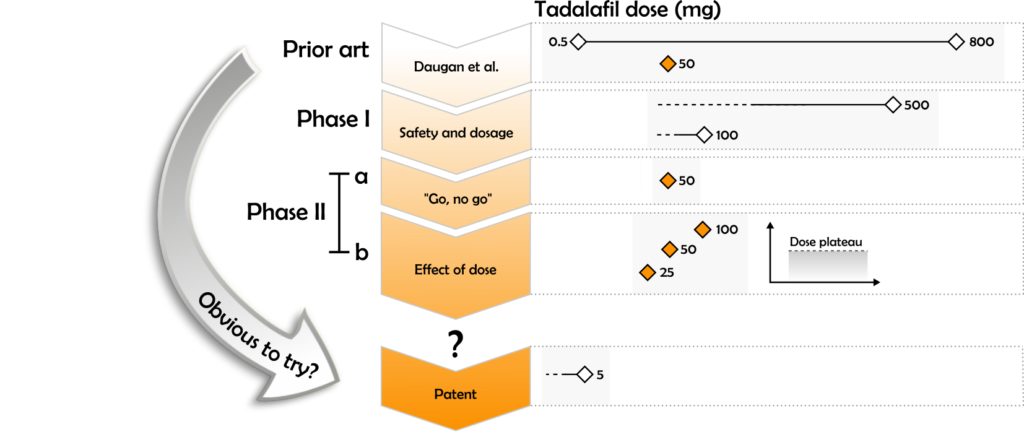

Daugan discloses the use of Tadalafil for the treatment of sexual dysfunction, at doses in the range of 0.5 to 800 mg daily, and provides data for use of a 50 mg dose. Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal concluded that the patent claims differed from Daugan, and were therefore novel, because Daugan does not disclose a dose of 1 to 5 mg per day of Tadalafil as an effective treatment of sexual dysfunction.

With regards to the inventiveness of the patent claims, it was also accepted by both courts, that given the blockbuster success of VIAGRA, the disclosure in Daugan that Tadalafil can be used to treat sexual dysfunction would highly motivate a skilled person to pursue Tadalafil in clinical trials.

From what is currently known regarding the established dose effects of Tadalafil, it was also accepted by both courts that routine experimentation in a Phase I clinical trial would establish 500mg and 100mg as the maximum one off and daily chronic dose of Tadalafil respectively. From such a result, it was also accepted by the parties and both courts, that routine practice would lead a skilled person to select a 50mg dose of Tadalafil for a subsequent Phase IIa efficacy study. Having established the safety and efficacy of a 50 mg dose, it was further agreed that a skilled person would then reasonably be expected to try doses of 25, 50 and 100mg in a Phase IIb dosage study (see below).

However, if the skilled person carried out the Phase IIb trial, published data indicates that they would have been faced with the surprising discovery of a dose plateau within the 25-100mg Tadalafil dose range, i.e. within this range, increasing or decreasing the dose does not significantly affect the efficacy or tolerance to the drug. The point of departure between the claimants and the defendants, as well as the High Court and Court of Appeal, was over what a skilled person would be expected to do following this result, and in particular whether it would be obvious to a skilled person to then try lower doses.

The High Court concluded that, following a hypothetical Phase IIb clinical trial demonstrating a dose plateau in the range of 25-100mg, it would not have been obvious to a skilled person to try doses lower than 25mg. The High Court Judge reasoned that, given that a Phase IIb trial would have ascertained a 25mg dose of Tadalafil as both safe and effective, a skilled person would not be motivated to investigate doses lower than 25 mg. The High Court concluded that it would not therefore have been obvious to a skilled person to try a dose of 5mg.

The High Court also reasoned that, in view of the hypothetical Phase IIb trial data, a skilled person would believe that the minimum effective dose of Tadalafil would lie somewhere between 10 and 25 mg, in line with the pharmacokinetics of similar drugs such as VIAGRA. The High Court concluded that a skilled person would not have tried a 5mg maximum daily dose of Tadalafil for the treatment of sexual dysfunction with any expectation of success.

The Court of Appeal disagreed with the High Court’s assessment. In particular, the Court of Appeal concluded that, because the purpose of a Phase IIb clinical trial is to establish a dose response curve, a skilled person would be expected to perform further studies using modified dose ranges, such that a response curve could be determined, and would eventually try a dose of 5mg or lower. In other words, while it would not have been obvious to a skilled person to initially try a dose as low as 5mg in a hypothetical Phase IIb clinical trial, the results from a trial using higher doses would, as a routine matter, lead a skilled person to try the lower doses with a reasonable expectation of success, until they determined the lowest effective daily dose as 5mg.

Despite overturning the High Court’s judgment, the Court of Appeal nevertheless warned against the over-elaboration of the obvious to try doctrine. In particular, the Court of Appeal emphasised that while the results of pre-clinical and Phase I clinical trials may generally be expected to be inventive, the inventiveness of the results of a Phase IIb clinical trial, the purpose of which is merely to establish the dosage effect of a drug that has already been demonstrated to be safe and effective, is more questionable.

The results of clinical trials are perhaps particularly susceptible to falling foul of the doctrine of obvious to try, given that regulatory approval requires particular results to be obtained in a particular way, and it is therefore obvious to a skilled person to follow a particular route with a reasonable expectation of success. In this context, patent protection requires that a particular drug or dosage regime is surprisingly effective in order for it to be inventive. It will also be interesting to see how the doctrine of obvious to try may be applied to the inventiveness of drug candidates identified by systematic automated searches of a database of likely candidates.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.