07/03/2018

On Thursday 8th March 2018, events will take place around the world to the mark International Women’s Day (IWD). IWD has been going for over a century and according to the official website, is intended to be a day “to celebrate the social, economic, cultural and political achievements of women” and which “marks a call to action for accelerating gender parity“.

In 2018, whilst we can acknowledge the progress that has been made over the past century, gender gaps still exist across society. Working in the field of patents, we are all aware of the (in some cases drastic) shortage of women working in STEM subjects. But just how far are we from gender parity amongst patent inventors? In short, pretty far…

How many women inventors are there?

Each year, the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) publishes a report including a wealth of statistics regarding the filing of international (PCT) patent applications. In recent years, this report has included some facts and figures relating to the gender of named inventors for PCT applications. It is perhaps worth pointing out that the figures are not wholly accurate, since no gender information is provided by applicants at filing; however, WIPO has invested a seemingly huge effort in compiling a worldwide gender-name dictionary, including 6.2 million names, to enable a gender analysis of patent inventors.

WIPO’s most recent report, published at the end of 2017, found that in 2016 the share of PCT applications with one or more women inventors was 30.5%, with the share of women-only PCT applications being around 5%. Whilst still relatively low, this reflects an increase of almost 10% since 2002, with the total number of women inventors almost tripling during this period. Back in 1995, the share of PCT applications with one of more women inventors was as low as 17%, so clearly progress is being made, albeit slowly. However, according to WIPO, at the current rate of progression, we are unlikely to see gender parity before 2080.

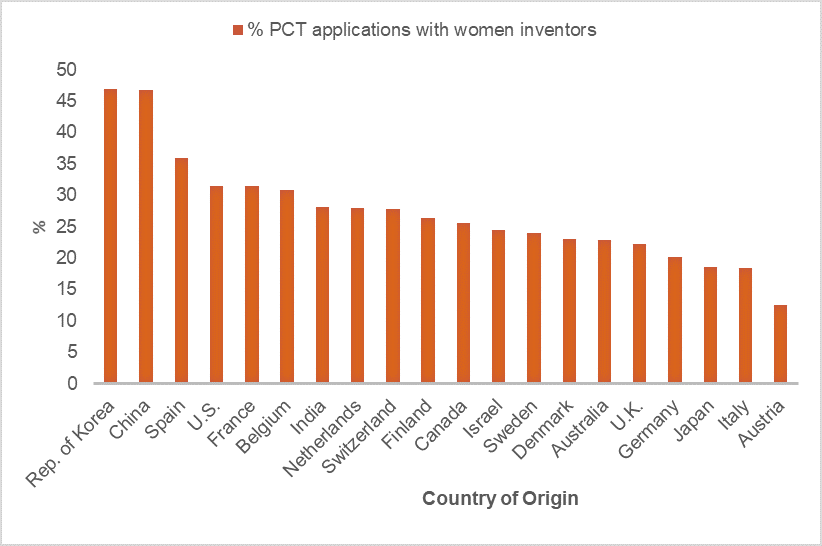

The value of 30.5% represents a global average but in fact, there are considerable, and in some cases surprising, differences in the share of PCT applications with women inventors across different countries. Amongst the top 20 PCT filing countries, China and Korea lead the way with almost 50% of PCT applications from these countries including a woman inventor. At the other end, the largest gender gaps are seen in Austria, Italy, Germany and Japan, with the UK coming in close to the bottom at 22% (see below). According to the WIPO report, the share of UK national patent applications with at least one woman inventor stands even lower, at around 15%.

Source: WIPO Statistics Database September 2017

Why are there so few women inventors?

There is a large amount of literature exploring the potential reasons for women’s current under-representation in patenting. Perhaps the most intuitive explanation of the gender gap in patent inventors is the gender gap in STEM fields: in the UK, women account for around a quarter of the STEM workforce and only 11% of engineering professionals (the lowest in Europe). Whilst at school, girls outperform boys across most STEM subjects up until the age of 16, after this there is a huge drop off in the number of girls studying core STEM subjects and only 9% of girls (compared to 29% boys) go on to do a degree in maths, physics, computer science or engineering. The reasons for this are too varying and complex to discuss here.

Clearly, therefore, it is seen as crucial to maintain efforts to get more girls to pursue STEM subjects at the higher education level and in particular, what are sometimes referred to as “patent-intensive STEM subjects”, which include engineering and computer science. However, whilst there is a clear correlation between the number of women obtaining STEM degrees and the number of women inventors, recent studies suggest that the gender gap in STEM education may not in fact be the main driver of the gender gap in commercial patenting rates. It has been shown that even within the STEM workforce, women are patenting at a significantly lower rate than men, indicating that there are other important obstacles that need to be removed in order to move closer to gender parity.

Entire papers can, and have, been written about the potential reasons for the lower patenting rate amongst women within STEM subjects, but in brief these are believed to include:

- Support structures within organisations: an overall lack of encouragement and support for women in academia and industry is thought to explain some of the productivity gap and the lower position of women within the academic hierarchy.

- Networks: women scientists have less access to extensive professional networks and the networks they do have contain fewer experienced scientists. Networks have been shown to be important for inventors’ entry into and negotiation of the patenting process.

- Stereotype threat: women are far more likely to experience gender bias from managers and perceptions of negative stereotypes are common, which can push women out of STEM careers.

- Workplace environment: women are more likely than men to transfer from technologically oriented positions to more socially oriented positions within a company, often to find a more ‘inviting environment’.

- Caregiving obligations: women are currently likely to be responsible for a larger share of caregiving obligations than their male peers, which may lead them to seek work demanding fewer hours. Women with children have been found to be less likely to patent than their male counterparts.

Whilst it’s easy to be cynical about some of these hypotheses, what seems undeniable is that in order to bridge the current gender gap in patenting, there needs to be not only an increase in women in STEM fields, but also a wider cultural shift in attitudes towards women working in innovation.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.