24/10/2018

Since the landmark UK Supreme Court decision in Actavis v Eli Lilly ([2017] UKSC 48), judges of the lower courts have voiced the need for clarification from the Supreme Court. In a Court of Appeal decision published recently, Icescape v Ice-World ([2018] EWCA Civ 2219), Lord Kitchin, who has been recently elevated to the Supreme Court, applies the principles of Actavis. This article considers whether there are any hints in this decision as to how Lord Kitchin may approach the unresolved issues raised by Actavis in the Supreme Court.

The Invention – Cooling apparatus for mobile ice rinks

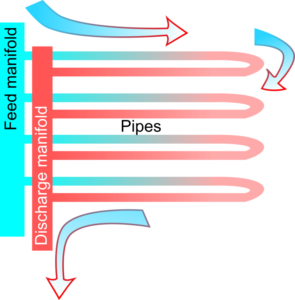

The case at issue was whether Ice-World’s patent for a mobile ice rink cooling member EP (UK) 1462755, was valid and infringed by Icescape. Mobile ice rinks are formed from an arrangement of manifolds and longitudinal pipes. Coolant pumped through the pipes freezes surrounding water to form the skating surface. The apparatus of pipes and manifolds has to be assembled each time the mobile ice rink is installed.

The cooling member for a mobile ice rink claimed by the patent comprises the standard manifold and pipe arrangement, organised into discrete elements. Each element comprises a feed manifold, a discharge manifold and a number of longitudinal pipes. In operation, the elements are connected in series by fluid-tight junctions between their respective feed and discharge manifolds. The pipes within each element comprise at least two rigid sections connected by movable fluid-tight junctions. These junctions allow groups of pipes to be folded against each other, so as to compact the apparatus for transport.

A question of priority

The first question to be decided by the Court of Appeal was whether the patent claim was entitled to priority.

The patent claims priority from NL1022998. The priority document differs from the granted patent in that it does not explicitly disclose a cooling member having multiple “elements”. The question was therefore whether a disclosure of the cooling member lacking the multiple element structure (but all the other features of the claimed member), was nevertheless a disclosure of the claimed invention (Article 87(1) EPC)?

The patentee argued that the inventive concept of the invention is the foldable pipes. This feature is clearly disclosed by the priority document. The patent merely discloses a further diagram showing one kind of common general knowledge set-up, wherein two elements are placed side-by-side and connected in the conventional way. A skilled person, it was argued, would have thus read this feature into the priority disclosure.

To decide the question, Lord Kitchin referred to the decision of the The Enlarged Board of Appeal of the EPO in G2/98, which states that for a valid priority claim, a skilled person must be able to directly and unambiguously derive the claimed subject matter from the priority document. In the eyes of Lord Kitchin, this provided a clear answer to the question under consideration: “The claim to priority depends upon the express or implicit disclosure of those features in the priority document and, since there is no such disclosure, the claim to priority must fail”. As a consequence of the invalid priority claim, the patent was found invalid in view of prior use by the patentee.

Infringement – Applying the Actavis Questions

Despite the finding that the patent was invalid, the question of infringement was still considered.

The Defendant, Icescape, accepted that their mobile ice rink had all the features of the claimed member, except the feature requiring the feed manifold and the discharge manifold to be arranged in series. In the Icescape cooling apparatus, the feed manifold is not connected to the discharge manifold. The respective manifolds are instead arranged in parallel. In first instance proceedings, the High Court therefore found on the basis of this difference that the Icescape cooling system did not infringe the claim ([2017] EWHC 42 (Pat)).

However, the High Court decision was determined before the Supreme Court decision in Actavis v Eli Lilly, which, in the words of Lord Kitchin, established a “markedly different” approach to claim interpretation than that applied by the UK courts until then.

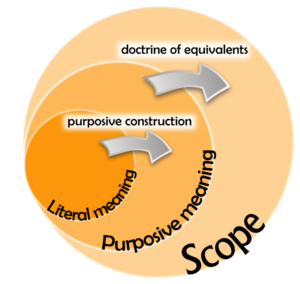

Lord Kitchin thus first reviewed the present case law on claim interpretation. He then set out the steps now required to interpret and determine the scope of protection of patent claims (provided in full below*). It must first be asked whether a variant falls under the scope of the claims by way of normal interpretation. Lord Neuberger’s “improved Improver” questions provided in Actavis must then be applied. Lord Kitchin called these the “Actavis questions”. It seems now well established, and was confirmed by Lord Kitchin, that when Lord Neuberger used the term “literal interpretation” in his Actavis Questions, he actually meant “normal (i.e. purposive) interpretation”.

Applying this approach to the case, Lord Kitchin agreed with the High Court that the Icescape cooling system did not fall under a normal (i.e. purposive) construction of the claims. A skilled person would read the claim to mean that the different elements were connected in series. The Icescape system clearly does not follow this structure.

Lord Kitchin then applied the Actavis questions:

a) Does the variant achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention, i.e. the inventive concept revealed by the patent?

To answer this first question, Lord Kitchin looked to the patent’s inventive core. He identified this as undoubtedly being the provision of a fluid-tight flexible joint member. This feature allows the system to be readily folded for transport and distinguishes it from known cooling systems. By contrast, arrangement of discrete elements of the apparatus in series could be readily found in the common general knowledge. The element structure is therefore peripheral to the inventive concept. Lord Kitchin thus concluded by answering the first Actavis question in the affirmative.

b) Would it be obvious to the person skilled in the art, reading the patent at the priority date, but knowing that the variant achieves substantially the same result as the invention, that it does so in substantially the same way as the invention?

Lord Kitchin again did not feel this question presented any significant difficulty. It was clear to him that the Icescape system clearly worked in the same way as the claimed apparatus. Arranging the feed and discharge manifold in series did not effect how the cooling member performed its function.

c) Would such a reader of the patent have concluded that the patentee nonetheless intended that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent was an essential requirement of the invention.

Given that the inventive core of the patent did not reside in whether the fluid flows through them in series or in parallel, Lord Kitchin concluded that “[t]here is no reason why a skilled reader would have thought that strict compliance with [these features] was an essential requirement of the invention”.

This case therefore provides a clear example of how Actavis has swayed the balance in favour of a patentee, when it comes to the issue of claim scope. For Lord Kitchin, and the other judges that have so far considered Actavis, what matters now is less the meaning of the words in a claim, and more inventive concept that the claim seeks to protect.

What about prosecution history?

In Actavis Lord Neuberger ruled that, contrary to Kirin-Amgen v Hoescht ([2004] UKHL 46) a court may rely on the prosecution history to determine the scope of a patent, if this would unambiguously resolve a point or if it would be contrary to the public interest for the contents of the file to be ignored (paragraph 88). The lower courts have not yet identified any circumstances in which either of these conditions have been met.

Lord Kitchin continued this trend. The defendant submitted evidence from the prosecution history of the application (available here), showing that in response to novelty objection from the EPO, the claimant deleted claims that did not specify the multiple element structure of the cooling member (see the patent attorney’s letter to the EPO on 22 August 2008). The defendant argued that this showed an intention on behalf of the applicant to exclude variants lacking this structure from the scope of the claims. Lord Kitchin rejected this on the basis that “[i]t is impossible to determine whether the objection raised by the Examiner was a sound one”. Lord Kitchin further argued that:

“it is impossible to discern in the correspondence any suggestion that Ice-World was surrendering an ability to argue that [the relevant features] were inessential or that Ice-World was accepting that the scope of the claims did not extend to a system in which the feed and discharge manifolds are connected in parallel rather than in series” [paragraph 79].

Lord Kitchin concluded that the high bar for having recourse to prosecution history in order to answer a question of equivalents was not passed in this case. We continue to await, therefore, an example of where consultation of the prosecution history is considered acceptable.

Can a claim be anticipated by equivalence?

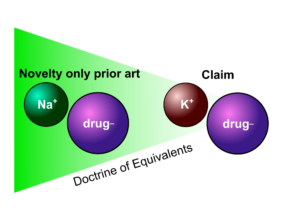

In a hypothetical situation, imagine a non-essential feature is introduced into a claim, for example to overcome a novelty-only prior art objection (Section 2(3) UKPA, Article 54(3) EPC), or as a disclaimer to overcome accidental anticipation. In such circumstances, the limiting feature may not relate to the inventive core of the invention. Applying the Actavis questions, the claim could thus be interpreted as including within its scope the very prior art cited against it. Such an outcome goes against one of the fundamentals of patent law (at least up until now), that you can not be granted a patent for that which is already known. In order to avoid this, does it follow that a claim may be anticipated by an equivalent?

In the wake of Actavis (which did not address this question), the issue of anticipation by equivalence was raised by Mr Justice Arnold in Generics v Yeda ([2017] EWHC 2629) and by Mr Richard Meade QC in Fisher & Paykel v ResMed ([2017] EWHC 2748). Both judges concluded that further clarification from the Supreme Court was required. In Icescape v Ice-world, the issue was not considered.

In the wake of Actavis (which did not address this question), the issue of anticipation by equivalence was raised by Mr Justice Arnold in Generics v Yeda ([2017] EWHC 2629) and by Mr Richard Meade QC in Fisher & Paykel v ResMed ([2017] EWHC 2748). Both judges concluded that further clarification from the Supreme Court was required. In Icescape v Ice-world, the issue was not considered.

Acting as a Court of Appeal judge, Lord Kitchin was bound to apply the principles of Actavis (“as [he] must”, paragraph 72). We eagerly await Lord Kitchin’s patent decisions in the Supreme Court.

A version of this article was first published on The IPKat.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.

* Lord Kitchin’s approach to claim interpretation and determining scope of protection:

‘66. i) Does the variant infringe any of the claims as a matter of normal interpretation?

ii) If not, does the variant nevertheless infringe because it varies from the invention in a way or ways which is or are immaterial? This is to be determined by asking these three questions:

a) Notwithstanding that it is not within the literal (that is to say, I interpolate, normal) meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent, does the variant achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention, i.e. the inventive concept revealed by the patent?

b) Would it be obvious to the person skilled in the art, reading the patent at the priority date, but knowing that the variant achieves substantially the same result as the invention, that it does so in substantially the same way as the invention?

c) Would such a reader of the patent have concluded that the patentee nonetheless intended that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent was an essential requirement of the invention

67. Of course, in order to establish infringement in a case where there is no infringement as a matter of normal interpretation, a patentee would have to establish that the answer to questions (a) and (b) above is “yes” and that the answer to question (c) is “no”.’