04/06/2019

Driverless vehicles have come a long way since the days of the DARPA Urban challenge, the US Department of Defence’s $2 million challenge to build an autonomous vehicle back in 2007. The challenge involved building an autonomous vehicle that could complete an urban track, while following traffic regulations and avoiding other cars. Out of 11 finalists, only 6 teams finished, with the winner averaging a speed of only 14 miles per hour.

Fast forward ten years to 2017 and Waymo, a subsidiary of Alphabet Inc, Google’s parent company, launched their early rider program, providing commercial rides in an autonomous vehicle to 400 people around the city of Phoenix. By mid-2018, Waymo’s fleet of driverless cars was driving more than 24,000 miles a day – the equivalent to a round-the-world trip. And Waymo are by no means the only company gearing up to make driverless cars a part of our every-day lives.

Just about every motor company out there is joining in the race to develop autonomous car technology, along with many companies not usually associated with the motoring world, such as Apple, Intel and Huawei. The inclusion of tech companies, alongside traditional motor companies such as Ford, BMW and Volkswagen, in the list of companies putting resources into driverless vehicles goes to show the vast range of technology that is being brought to bear on the problem. In a series of blogs, Reddie & Grose LLP’s autonomous and electric vehicle team will explore some of the key technologies that will be crucial to the successful development of commercial autonomous vehicles, starting with LIDAR.

LIDAR – Mapping out the Road Ahead

Many people may have seen the news story from the beginning of the year about a photographer’s camera being damaged by the LIDAR system on a driverless car at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, but what actually is LIDAR? If your first though is, “LIDAR sounds a bit like RADAR…” then that’s good – LIDAR means “Light RADAR”. The technologies function in a very similar way – where RADAR uses radio waves that are reflected back from an object in order to detect that object, LIDAR uses lasers.

One of the major advantages of LIDAR is that LIDAR systems can have centimetre resolution over large distances, up to 100 meters, and Waymo’s system can even detect the direction that a pedestrian is facing to help predict their likely movements. Most companies developing autonomous vehicle capabilities, with the notable exception of Tesla, have been employing LIDAR as the basis for a network of sensors that allow the car to “see”. However, one of the major problems that will need to be overcome to enable successful commercialisation of driverless cars is the cost of LIDAR systems.

Currently, LIDAR systems can cost us much as $75,000 – far too expensive to be used on a commercial scale for consumer driverless vehicles. However, there are many companies, both start-ups and established tech and motor companies, that are working to bring down that price. While economies of scale will be one factor in bringing down the price of LIDAR, the biggest savings will no doubt come from technological advancements.

And LIDAR advancements can mean big money. As reported previously in our blog, Waymo received $245 million from Uber in compensation for stealing trade secrets relating to Waymo’s LIDAR technology. While this sounds like a lot, it isn’t even a sixth of the $1.8 billion that Waymo initially sought. Nevertheless, while Waymo didn’t try to protect all of their LIDAR developments with patents, they still do have a number of patents relating to LIDAR, and the value that they and others place in the technology can be seen in recent patent filing trends.

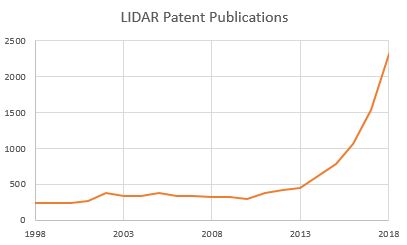

This graph shows the number of patent applications that have been published each year for the last 20 years, and have been classified under the International Patent Classification heading of “Systems using the reflection or reradiation of electromagnetic waves other than radio waves, e.g. lidar systems” (G01A 17/00) as well as either “Lidar systems, specially adapted for specific applications” (G01S 17/88), “for mapping or imaging” (G01S 17/89) or “for anti-collision purposes” (G01S 17/93).

As can be seen, in recent years the number of patent publications have increased year on year as companies attempt to protect their investments by obtaining patent protection for their inventions. These patents will be crucial for both the established players looking to fend of rivals and for new start-ups hoping to obtain investment and maintain their edge in a competitive market.

Some of the key LIDAR technology areas that many of these patents will be trying to cover are types of beam steering technology and distance measurement mechanisms, as well as the software for interpreting the measurements and ways to combine different types of LIDAR (and other) sensors to provide more information to a vehicle’s driving system.

Beam steering technology relates to how a LIDAR module “looks around”. The most common mechanisms include spinning LIDAR, mechanical scanning LIDAR, optical phased array LIDAR, and flash LIDAR.

Spinning LIDAR is what it sounds like: an array of lasers that is spun around at high frequency. This method has the advantage of 360 degree coverage, but comes with the drawback of involving a large number of moving parts. Mechanical scanning LIDAR, meanwhile, uses a moving mirror to scan an area with a fixed array of lasers. This has fewer moving parts than a spinning LIDAR, but also comes with reduced angular coverage. Optical phased array LIDAR uses a row of emitters and controls the direction of the laser. This solid state technology is relatively new, and provides for the prospect of LIDAR systems with no moving parts which could lead to long lifetimes and high reliability. Finally, flash LIDARS use a single laser flash to illuminate a large area at once, either from one wide angle laser or from multiple laser pointing in different directions. While such a system with a single laser will struggle to reach long ranges due to the power of the laser being spread over a large area, a multi-laser system could quickly become expensive due to the large numbers of lasers required.

Distance measurement methods are the different ways in which the laser light can be used to obtain a distance measurement. The basic approach is time-of-flight LIDAR which simply measures the time it takes for a laser pulse to leave the laser, travel to an object, reflect and travel back from the object, and be received by the LIDAR system. Other systems make use of a continuous wave, modulating its frequency or amplitude. While frequency and amplitude modulation require more complex electronics and processing, frequency modulation allows the velocity of objects to be measured, as well as their distance, while amplitude modulation is more resistant to interference.

It will be interesting to watch the development of these different approaches to LIDAR as the technology matures and is deployed on a commercial scale with the rise of consumer autonomous vehicles. Will it be the case that one LIDAR system accelerates ahead of the crowd to become dominant, or will different manufacturers utilise different types of LIDAR? Perhaps different types of LIDAR will be used together on the same vehicle to obtain the benefits of each. While it is impossible to say for sure which systems will succeed and which will be left behind on the curb, what is clear is that properly protecting the intellectual property developed in relation to LIDAR will be key to determining who the winners will be in this emerging market.

The autonomous and electric vehicle group at Reddie & Grose LLP has a great breadth of experience dealing with the different technological and commercial challenges faced by companies of all sizes, and can provide tailored advice to you and your company on how best to protect your ideas.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.