04/02/2020

Technology is generally regarded as the creation of something to improve one or more aspects of the world we live in. However, in the world of football (or soccer if you hail from North America), the introduction of video assisted refereeing is prompting many to question whether technology is actually ruining, instead of improving, the so-called ‘beautiful game’.

Some of the most recent criticism has come from English football, which saw the introduction of video assisted refereeing to the hugely popular Premier League in August 2019. So far, the biggest complaint concerns technology’s involvement in the offside rule, and in particular, the use of virtual offside lines (VOLs) to determine if “at the point a ball is kicked, any part of an attacking player’s body that can legally play the ball is ahead of the last field defender”, i.e. is a player offside?

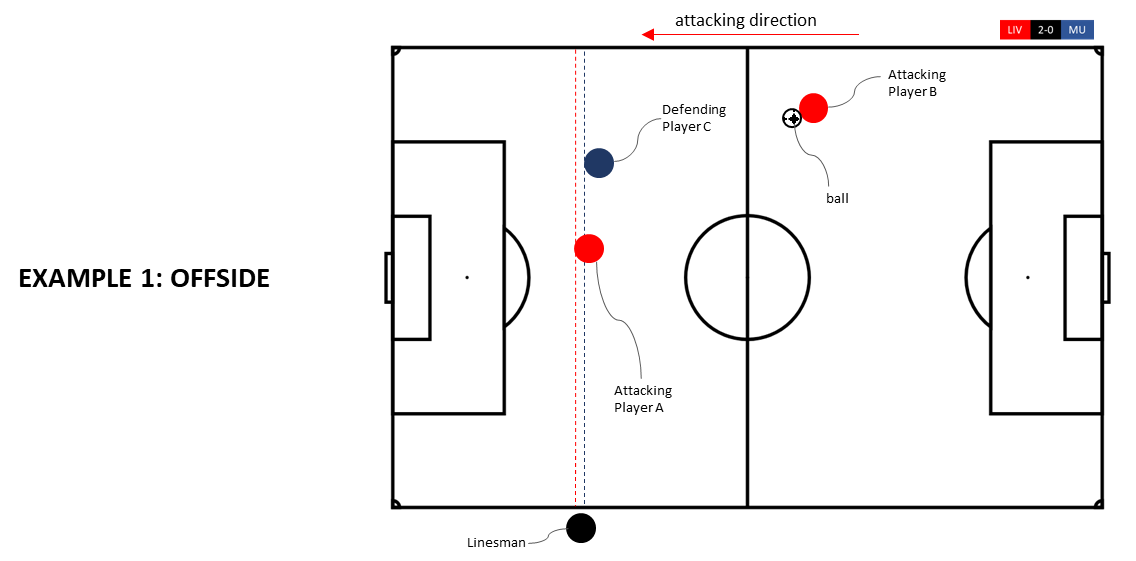

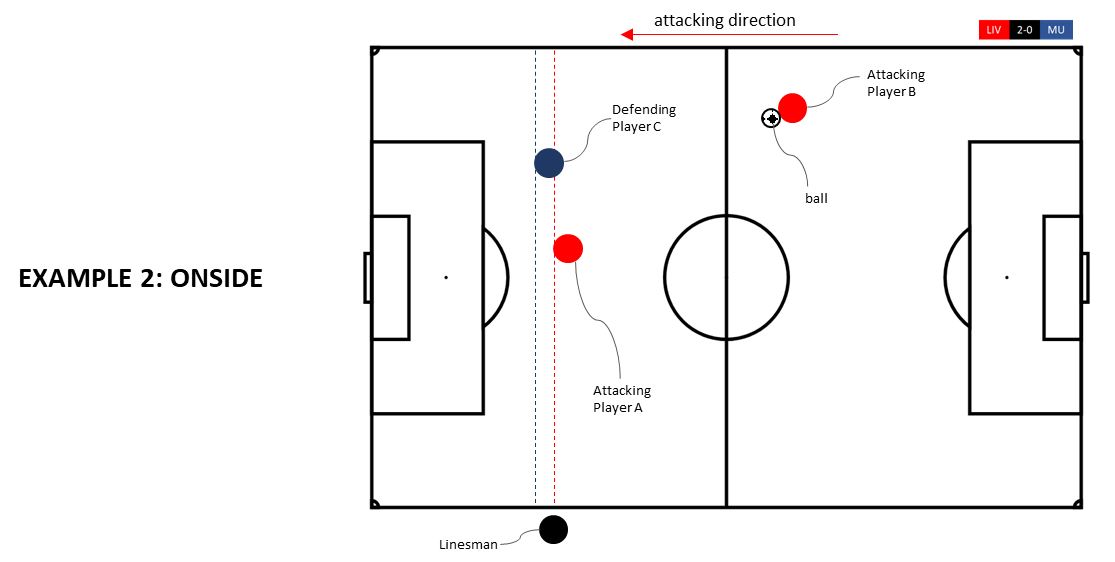

For those less familiar with football’s famous rule: Attacking Player A is:

- offside in Example 1 below when the ball is kicked by Attacking Player B; and

- onside in Example 2 below when the ball is kicked by Attacking Player B.

This is due to Attacking Player A’s relative position with respect to Defending Player C.

On the face of things, this is a simple principle and for years this law has been determined by the mere human perception of an assistant referee (linesman) standing at the side of a pitch. However, video assisted refereeing (VAR) now allows another remotely located assistant referee ‘the VAR’ to be involved. In their remote computer room, the VAR is allowed to review broadcast footage of an incident (such as a goal) and overlay virtual offside lines (e.g. the dashed lines above) onto the replayed images to determine if a player was offside or not.

In some instances, this has resulted in Premier League goals being disallowed on account of supposed millimetre differences in player positioning identified by the VAR. From Roberto Firmino’s armpit, to Jack Grealish’s heel, pundits and fans have spent countless hours complaining about the accuracy and appropriateness of such technology for ensuring the laws of the game are applied correctly.

So, how does the technology for VAR work, and is it really fair to criticise it?

Hawk-Eye’s Virtual Offside Line (VOL) System

The Premier League’s VAR technology is supplied by UK-based Hawk-Eye Innovations. Hawk-Eye are perhaps best known for ball tracking in tennis to determine whether a shot is ‘in’ or ‘out’; however, they also provide technology for many other sports including cricket, ice hockey, badminton and athletics. They also provide the much applauded and patented goal-line technology which has been used in the Premier League for over 7 years; interestingly, this goal-line technology involves minimal human decision making, and simply works by vibrating the referee’s watch within seconds of a ball crossing the goal line.

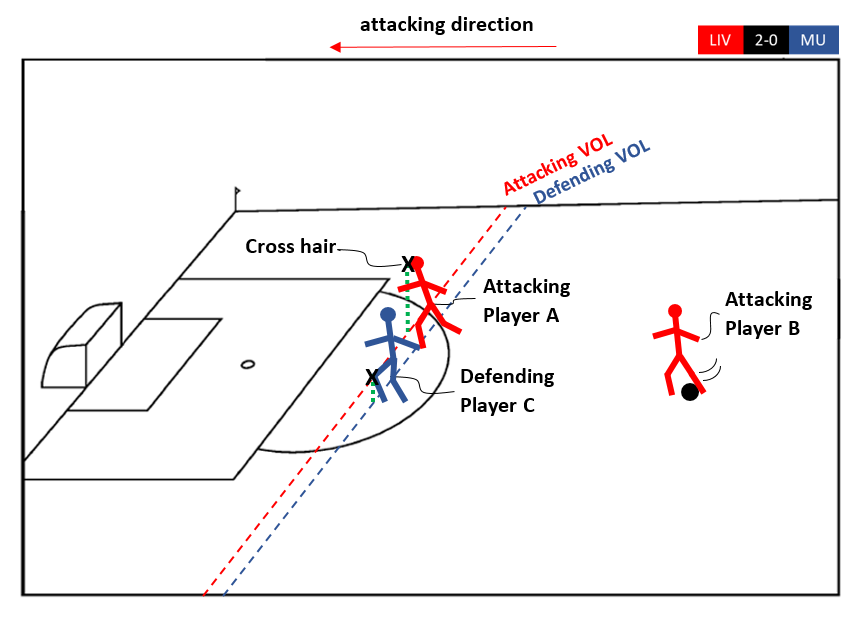

Hawk-eye’s VOL system, on the other hand, does involve some human input, and works by allowing the remote assistant referee (the VAR) to select the video frame where they believe the ball is first kicked. The VAR then positions a first cross hair on the furthest forward part of an attacking player, and a second cross hair on the furthest back part of a defending player. Each cross hair centres on a single pixel in the frame and draws a corresponding single-pixel wide vertical line, which descends to the pitch and mark’s the point for that player’s ‘virtual offside line’ (VOL). The VOLs are then drawn onto the image for the VAR to view and analyse.

In order to provide accurate VOLs, Hawk-eye’s system calibrates at least five high resolution broadcast cameras at specific points in the stadium, namely: a main wide camera, two 18-yard box cameras and two goal line cameras. The cameras are also synchronised with millisecond accuracy so that the same instance of footage can be viewed from multiple angles around the pitch.

At the start of the season, Hawk-eye also created a 3D model of each pitch in the Premier League, in order to map their exact topographies. This is important because football pitches are all designed with a slight bow or camber to help with water drainage – mapping this into the system enables the camber to be compensated for in the eventually drawn VOL. This means that some VOLs appear to bend when overlaid onto a broadcast frame, but these in fact correspond to a true accurate straight line for the pitch.

It would therefore be fair to say that the Hawk-eye system does provide an accurate tool for determining the relative location of players on a pitch. However, it is still reliant on human input, and this seems to be the root of much of the criticism. For example, it can often take several minutes for the VAR to review replay footage after a goal and determine whether an offside offence has occurred. During this time, fans in the stadium are left entirely in the dark, and fans at home are subjected to a painstaking experience of watching minute lines being drawn on a selection of still images.

Another major criticism comes again from the human element of the system in that it is often debatable which frame the VAR chooses as the one in which the ball is ‘first kicked’. The broadcast cameras operate at a rate of 50 frames per second, so the point of contact with the ball is taken to be one of those frames inside the 50 per second. But which one should it be? When a foot and/or ball are moving fast, they often appear blurry in the captured footage. Can the VAR really say with certainty that the ball is first kicked in frame X and not frame X+1, and could this affect the outcome of the eventual decision? When the relative positions of players can be determined with millimetre accuracy, the answer to the latter question is a resounding yes.

Because of these issues, many in football are calling for VAR to be scrapped entirely and arguing that it would be better to return to the traditional means of an onsite human linesman for instant decision making. However, this would (in my view) be an ill-advised step backwards. Instead, we should be looking to solve such problems by using more technology, not less, and some potential solutions are already being hinted at in the patent literature.

EP3457313 A1 – EVS Broadcasting Equipment (Belgium) – published March 2019

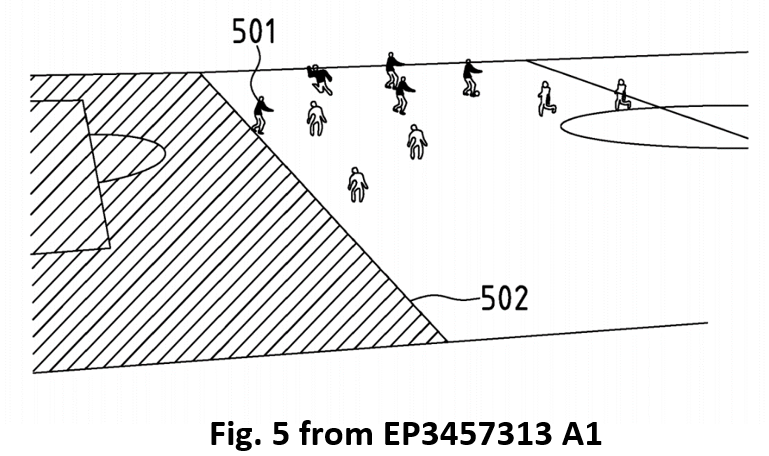

For example, European patent application no. EP3457313 A1 from EVS Broadcasting Equipment SA describes a computer-implemented system and method of: automatically mapping a reference view of a playing field from a camera; analysing each pixel to determine the positions of players (501) on the field; and positioning a line (502) in the view based on the detected position of the players. EP3457313 A1 notes that this system is capable of “automatically positioning an offside line in a soccer game without requiring manual interventions by an operator”.

In essence, EVS are working on a way of automatically drawing VOLs on broadcast footage in order to avoid undue manual input from a human VAR. This could considerably shorten the time needed to check for a potential offside after a goal has been scored, and thus alleviate some of the frustration felt by fans inside and outside of the stadiums. In November 2019, EVS announced that their AI-driven Xeebra product had successfully completed football governing body FIFA’s Quality Programme for Virtual Offside Lines. It would not be at all surprising if Hawk-Eye and others are working on similar AI-driven products.

EP3270327 A1 – Sony Corp (Japan) – published January 2018

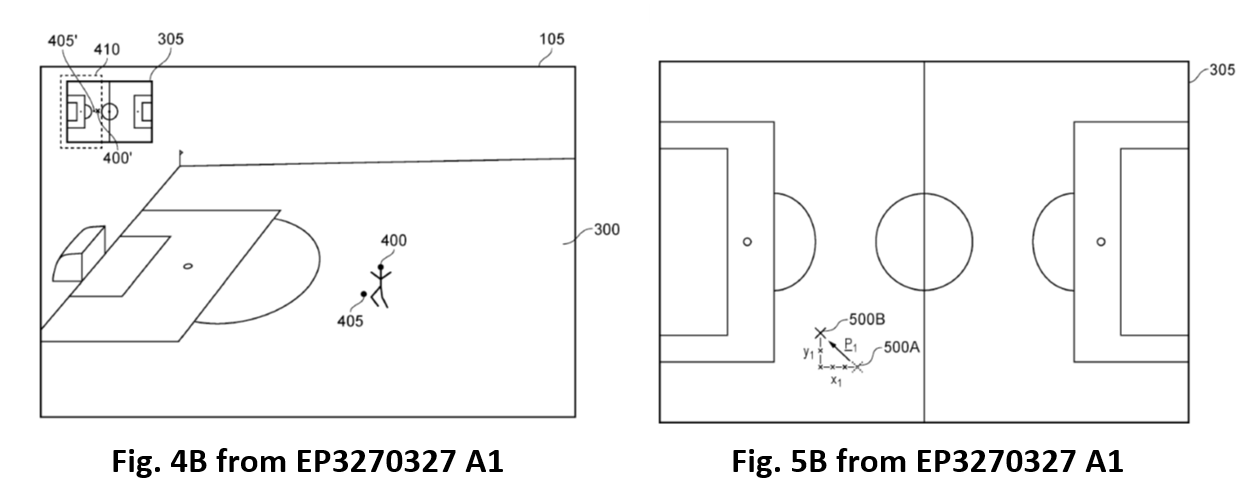

In fact, recent patent publications from Hawkeye’s parent company Sony Corp suggest that they are doing exactly that. An example of this is EP3270327 A1 which originates from three UK inventors and describes an object recognition system for tracking players and the ball.

The patent application mainly focuses on tracking individual players with automated cameras for enhancing spectator viewing and/or player performance analysis. However, it does also describe an automated method for predicting the position of players and the ball using vector-based analysis of their speed and acceleration. With such techniques it may be possible to interpolate the relative position of a player and the ball between frames of a video, and thus more accurately capture the exact moment a ball is first kicked. If executed properly, such a system would not only remove the subjective element of the human VAR deciding whether to pick frame X or frame X+1 for their analysis, but would also (presumably) shorten the overall time needed for the offside review process.

EP3457313 A1 and EP3270327 A1 are merely two examples of thousands of patent applications to have published in recent years in the field of sports analytics, and it is no surprise why activity in this area is so high. The English Premier League alone boasts annual global revenues of £5.2 billion, and annual global viewing figures of 3.2 billion. A lucrative trophy therefore surely awaits the eventual winner(s) of the VOL race.

The future of VAR

So what does the future hold for VAR? Well, with such potentially large rewards on offer, in time, it seems almost inevitable that we will have a system which provides a near-instantaneous objective decision on whether or not an offside infringement has occurred. In much the same way as Hawk-eye’s goal-line technology, by removing the slow and subjective human element from the decision making process, it is likely that fans and pundits will eventually come to accept and potentially embrace new and improved VOL technology. There will of course always be room for debate, and forever remain the philosophical question of whether it is right to only apply such high-tech driven standards at the upper echelons of the football pyramid, whilst still following traditional methods at all other levels. However, debate is and always has been part of what makes football football, and if we lost all reason to talk about the world’s favourite sport we might just find it becomes that bit less beautiful.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.