16/06/2020

Innovations in Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things are typically implemented in software and so can be challenging to patent at the European Patent Office. Firstly, patent protection for the invention must not be ruled out by the “software as such” exclusion of Article 52 EPC, and the invention must therefore solve a notional “technical problem”. Secondly, it must be possible to reduce an often complicated inventive concept to a single paragraph of text that can act as a patent claim. By way of illustration, this article looks at the patented smart home technology behind Nest Lab’s (“Nest”) learning thermostat, and explores how innovative start-ups can effectively protect their inventions.

Background and Technology

Nest was launched in 2010 by two ex-Apple engineers Tony Fadell and Matt Rogers with the initial aim of providing a networked thermostat for smart homes. The company since expanded into smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, and has also added cameras to its product range. Nest was bought by Alphabet (Google’s parent company) in 2014 for $3.2 billion, and has been since merged into Google.

Nest’s key innovation is its learning thermostat, which is able to learn the preferred home temperatures of its owners, factor in the thermal response of the home it is heating, and program a weekly schedule that saves energy. The home heating sector remains a large contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. By providing a real saving on energy bills, for those who cannot figure out how to properly program their home heating systems, Nest’s learning thermostat also enjoys significant green credentials.

But does it solve a technical problem?

Learning Thermostat

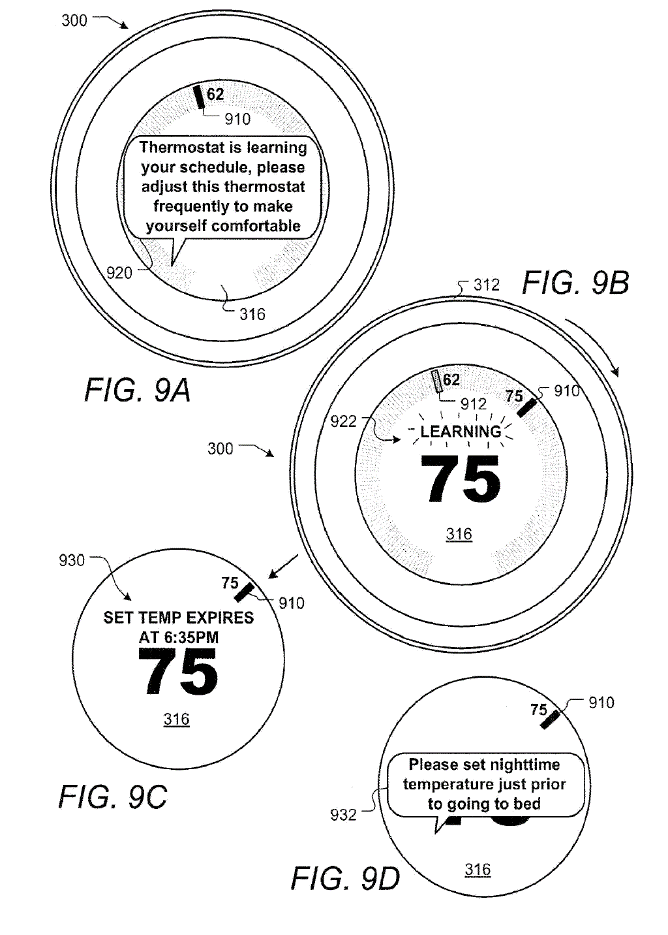

Granted European patent EP2769279B titled “Energy Efficiency Promoting Schedule Learning Algorithms For Intelligent Thermostat” aims to “learn” how to heat your home efficiently. Essentially, innovative programming in the thermostat encourages the user to interact with it by repeatedly setting the temperature set point back to a lower more energy efficient setting. From these repeated interactions, the thermostat can build up confidence in the appropriate set points for the home for particular times of day. It’s a bit like an automated version of a thrifty family member, but one that remembers, adapts and subsequently acts on the information it has learnt.

Patent protection is limited by the definition of the invention in the claims, and in this case, the claimed invention provides definition of both the networked hardware (the wall unit with a rotational input mechanism and display, temperature sensors and so on), and the necessary software functionality that guides the user and controls a connected HVAC (Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning) system.

Specifically, the software functionality is configured (in the wording of the claims) to: “identify a user’s desire to immediately change the setpoint temperature value to a more energy-consuming temperature based on the tracked rotational input; automatically reset or set-back the user’s setpoint temperature value to a less energy-consuming temperature after a predetermined amount of time; and generate a schedule for the thermostat based at least in part on repeated identifications of the user’s desire to immediately change the setpoint temperature”.

This concept is partly illustrated by Figure 9 of the patent reproduced below.

Patent claims typically provide only generalised definitions of what is believed to be the underlying inventive concept, often focussing on a single key feature of the invention, or a single bottleneck in a process that the invention puts into effect. It is not therefore unusual for a patent claim to be silent about the detail of the underlying technology which ultimately allows the invention to be performed, and in this case, Nest’s claim does not need to specify how the software thermostat “generates the schedule” once it has performed the interactive learning process defined by the set-points with the user.

Instead, the implementation in software is understood to be within the realm of the skilled computer programmer once they have understood what the patent description teaches them, and in this case, the focus of the invention is the interaction of the user with the device and the automatic control of the set points to learn what to do. The description notes:

While simply observing and recording a user’s immediate-control inputs can be useful in generating a schedule and/or adjustments to an existing scheduled program, it has been found, unexpectedly, that the thermostat can more effectively learn and generate a scheduled program that makes the user more comfortable while saving energy and cost when the user is periodically urged to input settings to maintain or improve the user’s comfort. Bothering the user by periodically urging manual input may at first appear to run counter to a user-friendly experience, but it has been found that this technique very quickly allows the thermostat to generate a schedule that improves user comfort while saving costs.

The notional technical problem solved here is therefore the reading of temperature sensor inputs indicating ambient air temperatures in the home, and controlling an associated HVAC system based on specific prompts to the user to establish preferred temperatures and generate a control schedule. Although this innovation was enough to earn Nest a European patent for its smart home technology, the jury is out on whether it defuses household arguments about who controls the thermostat and decides how warm the home should be.

Front End / Back End

As well as the European patent discussed above, Nest have a further two granted European patents relating to the “front-end” functionality of the learning thermostat. European patent No. EP2831687 relates to the display of technical information (in this case usage information) about the home heating system, while European patent No. EP2769277 acts to determine when a resident is away from home so that the thermostat can drop back to an away-state setting. In addition to these “front end” patents, Nest have European patent protection covering the invisible or “back-end” aspects of the system. These relate to improvements in the underlying digital communication aspects of the network of smart devices, and to device safety and management.

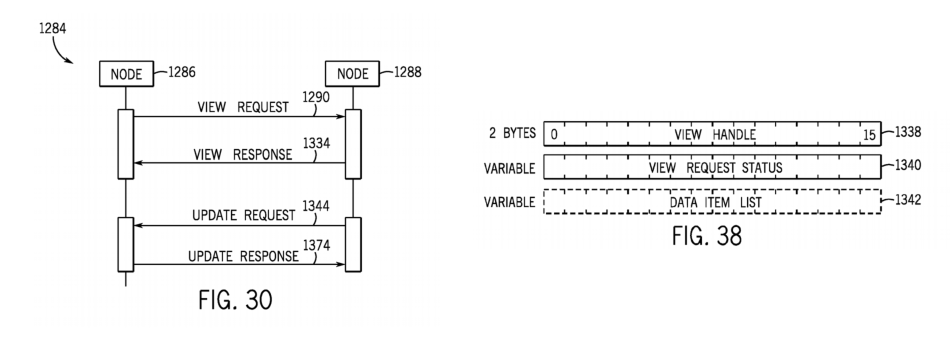

European patent No. EP2978166 for example relates to an IoT “fabric network” coupling electronic devices using one or more network types. The devices include door sensors, appliance sensors, environmental sensors and so on, which may operate with different network requirements such that communication between them is difficult. The invention addresses this by providing a data format and schema (e.g. a compact description for a data item) for communication between the different devices. Although the data format and schema are abstract in nature, they can be claimed in terms of a characteristic exchange between two electronic devices in the network. The claim expresses this as follows:

generating a view request message (1290), wherein the view request message (1290) comprises: a view handle field (1294) to identify the requested view; and a variable length path list (1298) configured to indicate a schema path, the schema path being a description for a data item or container on a node; transmit the view request message (1290) via the electronic device (10) through a fabric network over a platform layer (100); receive a view response message (1334) based on the view request message (1290), wherein the view response message (1334) comprises: a view handle field (1338), the view handle field (1338) containing a value that matches a value of the view handle field (1294) transmitted in the view request (1290) through the fabric network; and a view request status (1340) configured to indicate a status of the view request (1290).

The result of the data format exchange defined above is that two or more devices in the fabric may communicate to update software protocols or request node-resident information stored in other devices (e.g. a current setpoint temperature) more easily.

Similarly, granted European patents EP2758843 and EP2641172 provide other improvements to the network. EP2758843 relates to updating software on the thermostats around the home, while EP2641172 discusses exchanging information between a network connected thermostat and a cloud based management server.

Summary

The European patents discussed above are by no means all of the granted patents owned by Nest Labs, and as well as a number of further applications pending in Europe, both Google and Nest have many more relevant patent applications and granted patents filed in the US. However, the patents discussed here provide a useful glimpse into the technology and some of the strategy behind the patent portfolio.

First, despite the software related nature of the technology, the inventions avoid the “software as such” exclusion of the European Patent Office by being set in the context of a wider “technical” system, one that accepts user inputs, involves sensors, and ultimately controls an HVAC. Alternately, the inventions relate to the interactions between a network of computer devices themselves, either exchanging data or updating software or control parameters. These are just two of the respective “technical” safe harbours in which patent protection for software is possible.

Also, the claims of the European patents demonstrate a number of key techniques for protecting innovative products implemented in software, namely focussing on concrete steps in the user experience rather than details of the underlying code (which once the inventive idea is understood may be straightforward to implement), or defining the logical parameters in a data exchange format and writing a claim that defines a single transmission and receipt of data using the protocol.

Lastly, Nest’s approach also demonstrates that successful commercial products are often protected by several patents, approach the inventive idea from different directions and attempting to seek patents for different aspects of the product, both “front end” user facing functionality as well as “back end” aspects of data exchange and network functionality.

Reddie and Grose LLP’s AI and IoT group has considerable experience in protecting innovations in this space. If you would like more information, please contact us.

Links:

Nest Learning Thermostat: “Programs itself. Saves energy”

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.