18/09/2017

2017 marks the 400th anniversary of GB1, the first patent granted in England. Well, sort of.

Although the very first UK trademark has become a pub quiz staple (the Bass red triangle for Pale Ale), the subject of the first patent is much less well known. This is largely due to UK Patent Law’s long and somewhat murky history. In fact, GB1 is not really a patent at all, at least in the modern sense, and its selection as the first in the sequence owes more to chance than anything else.

The famous Bass triangle

In 1852 the newly established Patent Office set about publishing patents granted before that date. In doing so, the Patent Office retrospectively assigned numbers to historical patents according to their approximate grant date as listed by a docket book. GB1 was the first patent in that docket book, having been granted in 1617. As a mental yardstick, this predates Newton’s three laws of motion by about 60 years. However, 1617 was by no means the dawn of the patent system. In England, the Crown had granted patents at least as far back as the 15th century; 1617 was merely the earliest patent recorded in the leger chosen by the Patent Office.

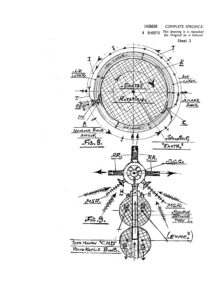

GB1 was not therefore the first patent granted in the UK. To further dampen the sense of occasion, GB1 is not even a patent as we understand the term. This is because the early “letters patent” were not patents for inventions, as is the case now, but monopolies granted by the Crown for making and/or selling certain commodities. GB1 describes a monopoly granted to Rathburn & Burges for “Engraving and Printing Maps, Plans, Etc.”

GB2 – granting a monopoly for reproducing images of the royal family

Unfortunately, monopolies granted by the Crown were increasingly awarded to favoured individuals for activities that were being performed already rather than for making and selling new things. This caused numerous disputes, for example the “Case of Monopolies” court case (Darcy v Allin, 1602) which revolved around a monopoly for selling playing cards.

The landmark 1624 Statute of Monopolies was introduced as an instrument for reform, and removed the Crown’s power to grant patents as well as requiring patents to be granted only for ‘any manner of new manufacture.’ The Statue of Monopolies was the first step towards the modern patent system and laws in force today.

Much has changed in the four centuries since the grant of GB1, and to celebrate the dramatic progression of technology and patent law in that time, I have selected a few personal highlights from the UK patents archive.

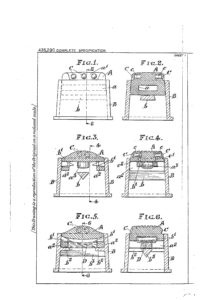

Best UK Invention: the Catseye (GB436290, 1933)

Although the title of “best invention” is hugely subjective, Mr Peter Shaw’s Catseye ticks the boxes of being useful, successful and ingenious and was voted the greatest invention of the 20th century. The inspiration for the invention apparently came from Mr Shaw realising he had been using reflections from tram-tracks to stay on the road during the night.

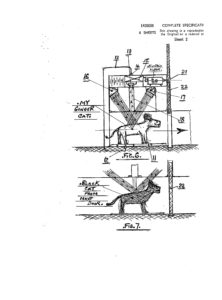

Most Eccentric UK Inventor: Mr Arthur Pedrick

Arthur Pedrick was a retired Patent Examiner who spent his later years tormenting his former employers. Mr Pedrick filed over 150 UK patent applications in the 1960s and 70s for inventions of varying degrees of usefulness. A strong contender for the most bizarre is Mr Pedrick’s patent for a “Photon push-pull radiation detector for use in a chromatically selective cat flap control and 1000 megaton earth-orbital peace-keeping bomb.” The application records conversations Mr Pedrick holds with his cat, Ginger, while developing a cat flap which will allow Ginger to pass through the flap while excluding cats with different coloured fur. It is Ginger who (apparently) suggests the same technology could be applied to a 1000 megaton earth-orbital peace-keeping bomb.

Worst UK Invention: Gold from Wheat (GB014204)

Without doubt the most disappointing patent was granted in 1884 to Harry Fell for “A New Method for Getting Gold from Wheat.” For amateur alchemists, or bored farmers with a bumper crop, this is how Mr Fell claimed gold could be obtained from wheat:

- Let the steep remain still for ten hours at 59 degrees Fahrenheit;

- Strain off the liquor into a shallow pan of some such cool substance, such as china or earthenware;

- Leave this liquor to stand in this pan for yet 24 hours at 60 degrees;

- Catch up the skin on some cool substance, such as china or earthenware.

Unfortunately, the best I have managed to produce is something approaching warm beer froth. Perhaps in the next 400 years someone will patent a use for that.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.