15/11/2017

The UK High Court has issued its first decision which considers the new doctrine of equivalents (DoE) approach established by the Supreme Court’s recent landmark decision Actavis v Eli Lilly [2017] UKSC 48 (reported here). In Mylan v Yeda, Mr Justice Arnold considers whether purposive construction should still be used to determine questions of infringement and to what extent the judgement affects the law on novelty.

Background: Actavis v Eli Lilly

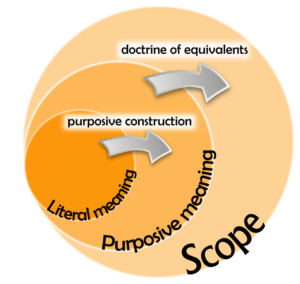

In Actavis v Eli Lilly, the Supreme Court ruled that a claim could be infringed by a variant that does not fall within the meaning of the claim but is equivalent to the claimed subject matter. The judgement departed from the longstanding approach of the UK courts, in which the validity and scope of a claim was determined by purposive construction, i.e. construing the meaning of the claim according to what the skilled person would have understood the patentee to have used the language of the claims to mean, as established by the House of Lords in Catnic v Hill [1982] and Kirin-Amgen v Hoechst.

In Actavis v Eli Lilly, Lord Neuberger separated, for the first time in UK law, establishing the meaning of a claim and determination of the claim’s scope. Lord Neuberger ruled that the scope of a claim should be determined according to a doctrine of equivalents (DoE), in which variants that achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the claimed subject matter are considered to fall under the claim’s scope, even if they do not fall within the meaning of the claim. For the case in question, Lord Neuberger held that, whilst the phrase sodium pemetrexed in a claim could not be interpreted to mean potassium pemetrexed, potassium pemetrexed fell within the claim’s scope because a skilled person would believe that potassium pemetrexed achieves substantially the same result as sodium pemetrexed in substantially the same way.

Determining the scope of patent claims per Actavis v Eli Lilly

Guidelines for determining infringement

Lord Neuberger provided the following guidelines for deciding whether a variant infringes a patent claim, in the form of the following three questions:

- Notwithstanding that it is not within the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent, does the variant achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention, i.e. the inventive concept revealed by the patent?

- Would it be obvious to the person skilled in the art, reading the patent at the priority date, but knowing that the variant achieves substantially the same result as the invention, that it does so in substantially the same way as the invention?

- Would such a reader of the patent have concluded that the patentee nonetheless intended that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent was an essential requirement of the invention?

If questions (1) and (2) are answered yes, question (3) is answered no, then the variant infringes.

Mylan v Yeda

In Mylan v Yeda, the claimants (Mylan and Synthon) sought revocation of the defendant’s (Yeda’s) patent directed to the use of a glatiramer acetate (GA) in a new treatment regime for multiple sclerosis, on the grounds that it lacked novelty and inventiveness in view of WO 2007/081975 (Pinchasi et al., “Pinchasi”). In the High Court decision, Mr Justice Arnold considered how the claims should be interpreted in view of Actavis v Eli Lilly, and whether an equivalent of the invention disclosed in the prior art should be considered for the purposes of novelty.

Purposive Construction versus Literal Interpretation

In Mylan v Yeda, Mr Justice Arnold considered whether, following Actavis v Eli Lilly, a patent claim should be given a purposive construction before the doctrine of equivalents is applied. This question arose because of Lord Neuberger’s reference in step i) of his guidelines provided in Actavis v Eli Lilly to the “literal meaning”, as opposed to the purposive meaning of the claims. In Mylan v Yeda, the defendant argued that, given this reference to the literal meaning of the claims, it was now the law that the claims should be interpreted literally in the same manner as a clause in a commercial contract. In response, the claimants submitted that Lord Neuberger also referred throughout his judgement to interpretation of the claims by the skilled person, and that the claims should therefore be given a purposive construction.

Mr Justice Arnold agreed with the claimant (paragraph 137). In particular, Mr Justice Arnold ruled that patents are not equivalent to commercial contracts and that, despite the reference to the literal meaning in i) of the guidelines, Lord Neuberger expressly stated elsewhere “that a patent was to be interpreted through eyes of a skilled person and that the exercise involved interpreting the words of the claim in context” (paragraph 138). Mr Justice Arnold therefore concluded that purposive construction should still be used to interpret the meaning of patent claims.

The Doctrine of Equivalents and Novelty

According to the long-established principle of novelty provided in Synthon v SKB, a patent is anticipated by a disclosure which, if performed, would infringe the patented invention. In Mylan v Yeda, the defendants argued that, in view of Actavis v Eli Lilly and the jurisprudence of the Board of Appeal of the EPO, Synthon v SKB no longer applied. In particular, the defendants argued that it follows from Actavis v Eli Lilly that a claim is not necessarily anticipated if the subject matter of the prior art would infringe the claim under the doctrine of equivalents. Mr Justice Arnold agreed with the defendant, but indicated that “it will require another decision of the Supreme Court to supply a definitive answer to the question” (paragraph 161). We await this further clarification from the Supreme Court.

For the case in question, Mr Justice Arnold ruled that the claims would lack novelty if the equivalent treatment regime described in the prior art were to be considered relevant for the question of validity. However, Mr Justice Arnold did not pursue the question further in view of his decision that, even if the claims were novel, they were not inventive in view of Pinchasi.

Summary

Mylan v Yeda is the first case in which the High Court considers the new doctrine of equivalents approach established by Actavis v Eli Lilly, in particular with regard to the effect of the judgement on claim interpretation and the law of novelty. Mr Justice Arnold’s opinion in the High Court judgement is that the disclosure of an equivalent in the prior art does not destroy the novelty of a claim. However, Mr Justice Arnold also identifies the need for further clarity from the Supreme Court on this issue.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.