31/10/2019

Significance

Last week the Supreme Court ruled that an inventor, Professor Shanks, was entitled to compensation for an invention he devised while employed by Unilever in the 1980s. A link to the ruling may be found here. Such successful decisions are extremely rare (there is only one other case, Kelly and Chiu), and this is the first time that the Supreme Court has considered this corner of the Patents Act.

The Supreme Court’s decision to overturn the rulings of the lower courts and award £2m to Professor Shanks is a landmark decision that could pave the way for further successful claims.

Background

While working for a subsidiary of Unilever (CRL), Professor Shanks had the idea of investigating re-usable or disposable devices incorporating biosensors for diagnoses. Drawing on his previous experience making LCD screens, Professor Shanks realised that the capillary action method used to fill small gaps between layers of an LCD screen could also be used with blood or urine samples for diagnostic measurements. Nearly 37 years ago to the day, Professor Shanks made a prototype at home with his daughter’s toy microscope set; the ensuing invention has enabled the development of disposable blood glucose testing devices and home pregnancy kits.

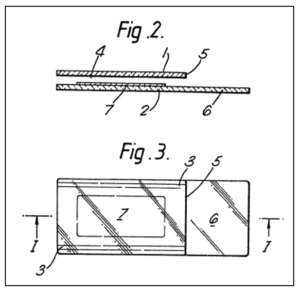

Figures from Unilever’s patent for Professor Shanks’ invention (EP0170375).

A sample applied onto platform (6) is drawn in between plates (1,2) into cavity (4) due to a capillary action and onto an layer (7) that provides an indication of whether a diagnostic test is positive or negative.

Unilever did not develop the glucose testing devices, as this was not an area in which they were well established, and instead focussed on developing home pregnancy kits, which were more aligned with Unilever’s existing businesses. However, Unilever expended a significant effort to obtain and then maintain patents protecting the glucose testing device concept even though they themselves were not developing such devices. This paid off in the following decades as the market for disposable glucose testing devices expanded rapidly. Unilever granted a number of licences, which were held to be worth £24 million.

The patents expired and in June 2006 Professor Shanks made a claim for compensation for his fair share of the benefit derived by Unilever. In doing so, Professor Shanks’ case was heard – and rejected by – three lower rungs of the legal ladder: a Hearing Officer before the UK Intellectual Property Office; the High Court; and the Court of Appeal.

The case was brought before the Supreme Court to determine two key issues: firstly, under what circumstances may compensation be awarded to employee-inventors; and, secondly, how should the amount of compensation be determined.

Entitlement to Compensation: “Outstanding Benefit”

Under the UK Patents Act 1977, an employee-inventor may be entitled to compensation if a patent for their invention is of outstanding benefit to the employer, having regard to (among other things) the size and nature of the employer’s undertaking. Historically, this requirement has been very difficult to achieve, not least for very large companies such as Unilever, whose turnover and profits dwarf the contribution of even an extremely lucrative patent, leading to accusations that some employers were “too big to pay”.

It was an established fact that Unilever’s net benefit from Professor Shanks’ patent was £24m, mostly derived from licensing agreements. In each of the preceding three court decisions, it was held that this amount did not constitute an “outstanding” benefit to Unilever.

The Supreme Court disagreed with the earlier judgements, ruling that the original decisions included an error of principle. At the heart of this ruling was Unilever’s complex corporate structure, whereby Professor Shanks was employed by a small Unilever subsidiary (CRL), but the patents were licenced to other subsidiaries, Unilever plc, Unilever NV and Unilever Patent Holdings BV. The Supreme Court held that the lower courts had cast their net too widely by considering the “employer’s undertaking” to constitute the Unilever group as a whole, rather than the entity that actually employed Professor Shanks.

Thus, the Supreme Court held that the benefit of the patent must be assessed against the benefit to the Unilever group (the employer as a whole) provided by other patents produced by the same group that employed Professor Shanks (i.e. CRL). In this context, and considering a number of other factors, the amount of £24m was held to be exceptional.

By assessing the benefit of other patents derived from CRL, the Supreme Court attempted to ensure that the benefit of the patent was assessed against a fair benchmark, rather than other misrepresentative benchmarks, for example the overall turnover of the Unilever group, or other successful products that originate for other subsidiaries, and which may have a value that is not wholly attributable to an underlying patent (for example, due to advertising).

How Much Compensation: “Fair Share of the Benefit”

Having established that the benefit to Unilever amounted to £24m, and that this amount was exceptional, the Supreme Court turned to how much of this benefit would be a “fair share” for the employee to be awarded.

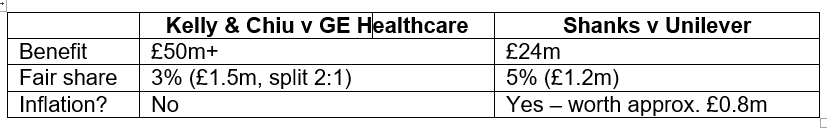

As alluded to above, there is only one other precedent for awarding compensation to an employee-inventor: Kelly and Chiu.

In Kelly and Chiu, the judge (Floyd J.) said they had no difficulty in deciding that the patents had been of outstanding benefit to Amersham (GE Healthcare). The judge went on to determine that the value of that benefit was at least £50 million and that the two inventors, between them, were entitled to a 3% share of this. However, the judge noted that a fair share of the benefit may in principle lie between 0% to 33+% (based on the fact that 33.3% is the amount awarded to academic inventors under the Biological and Biotechnological Sciences Research Council industry scheme).

Dr Kelly, who directed the research and was one of the first human test subjects for the new imaging agent at the heart of the patent, was awarded £1 million while Dr Chiu, a more junior employee but a very able synthetic chemist, was awarded £500,000. The judge noted that the benefit and fair share estimates were quite conservative but considered that the final award, which represented about three days’ of the employer’s profits, was just and fair in light of all of the evidence.

In the present case, although the Hearing Officer found that there was no outstanding benefit, it was decided at first instance that a fair share of the benefit would have been 5% of the royalties derived by Unilever. Although this was reduced during appeal to 3%, the Supreme Court held there was no basis for doing so and that Professor Shanks was entitled to 5% of the £24m; i.e. £1.2m.

In addition, the Supreme Court held that this amount should also be adjusted for inflation in consideration of the fact that Unilever acquired the licensing revenue between 1996 and 2004. In the view of the Court, Unilever had the benefit of the licence fees from then until the present day and that fairness demanded that the compensation awarded would reflect the “detrimental effect of time on money”. Accordingly, an average rate of inflation of 2.8% was applied from a median year of 1999 up until 2019 in order to arrive at the final award of £2m. This illustrates the substantial impact of the time value of the benefit, which had the effect of increasing the compensation by over 60%.

Conclusion

Although this decision is welcome news for inventors, it is unlikely that this decision will open the door for many other employee-inventors to seek compensation, as an employee’s invention must still be regarded as being “outstanding” to their employer’s undertaking.

In addition, when making a claim employee-inventors may not find it as easy to separate the value directly attributable to a patent from the value of a product. In this case, this consideration was simplified by Unilever choosing not to commercialise the patent, meaning all profits derived from the patent were directly attributable to licensing deals or sale of the patent to a third party.

Finally, the Supreme Court have offered useful guidance on how to assess whether a patent is of outstanding benefit, particularly in the context of a large company with multiple revenue streams.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.