24/12/2019

Predicting the future is a fool’s game at the best of times, but in the current turbulent and fast-changing world it is perhaps even more so. Nevertheless, let’s try and use the patent system as a crystal ball in an attempt to at least see the directions that the automotive sector are heading in.

Although patent applications are published, and therefore become publicly available, 18 months after they are filed, they can still be used as a good indicator of where R&D is being carried out, and so what future products might look like. In the automotive sector, where the development time between a blank sheet of paper and being in a vehicle on the market can be considerable, the publishing of a patent application will often be the first indication of what companies are working on.

With that in mind, let’s have a look at the potential future of technology in autonomous electric vehicles, by firstly looking at the “electric” part, and then secondly the “autonomous” part.

Before we begin though, some calibration …

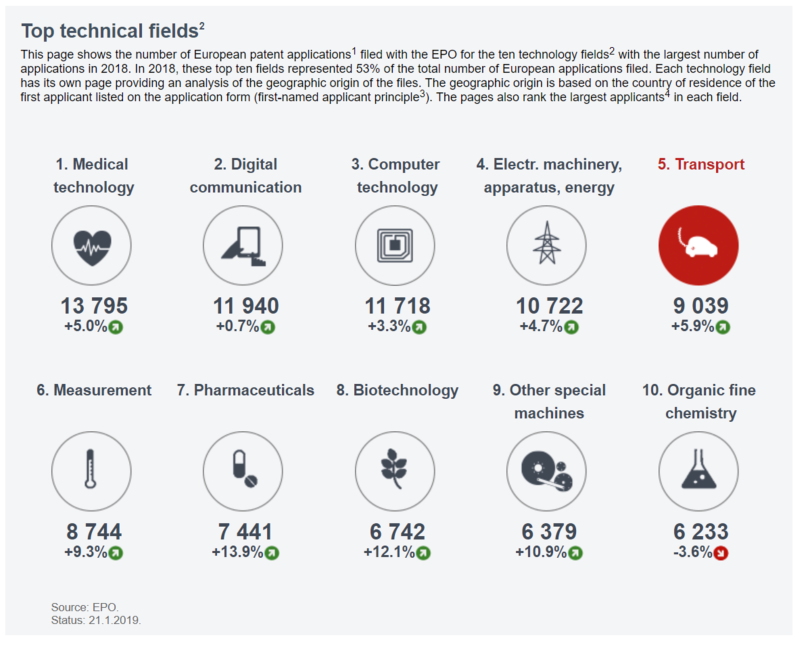

The European Patent Office publishes an annual report showing filing statistics and trends. In 2018, nearly 175,000 European patent applications were filed, about 9,000 of which were in the “Transport” technical field (see an extract below from the EPO’s 2018 annual report). However, this is likely not the full picture of patent filings in the autonomous electric vehicle sector, given other technology fields, such as “Electrical machinery, apparatus, energy”, “Other special machines”, “Digital communication”, and “Computer technology”, will no doubt include relevant patent filings. Given this, it seems that somewhere between 5% and 30% of patent filings in Europe, and by proxy the world, are likely at least tangentially related to this sector.

Figure 1. [EPO Annual Report 2018]

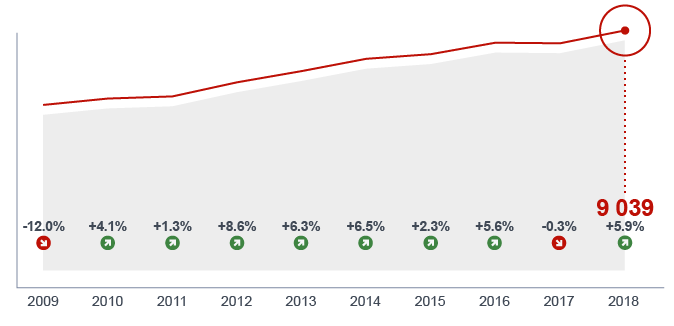

If we look at the Transport sector patent filings in Europe over the previous 10 years, we see an average growth of around 4% year-on-year. This is our baseline growth to which we can compare the growth in the specific technologies related to autonomous electric vehicles.

Calibration over, on to the specifics …

We conducted searches for patent publications in Europe, the US, Japan, China, and also International (PCT) patent publications, as a proxy for worldwide patent publications, in various patent classifications related to autonomous electric vehicles. We eliminated duplicates, i.e. a patent filed to an invention in the US and Europe would only be counted once, so that the numbers should be an approximation of the number of inventions.

We broke down the “electric” part into the key components of an electric vehicle powertrain, Batteries, Controllers, and Propulsion, and the “autonomous” part into Image Analysis + LiDAR, Control of Position, and Collision Avoidance.

Let’s look firstly at “electric” part, and start with Batteries. Figure 2. shows the patent publications over the past ten years in the patent classification IPC H01M – “Process or Means, e.g. Batteries, for the direct conversion of chemical energy into electrical energy”.

Figure 2.

As you can see from Figure 2, there has been a huge amount of growth in this technology area, from just over 40,000 patent filings in 2009 to nearly 100,000 in 2018 alone. This represents well over 8% year-on-year growth over this time period, and so significantly more than the 4% baseline.

What we can take from these results, which is perhaps as expected, is that a huge amount of R&D is being carried out in this area. I should note that equating numbers of patent publications with R&D spend is clearly not an ideal analogy, because there other many other factors that will influence the number of patent filings per $ of R&D spend. Nevertheless, it is clear that in order to file a patent application, a certain amount of R&D must have taken place.

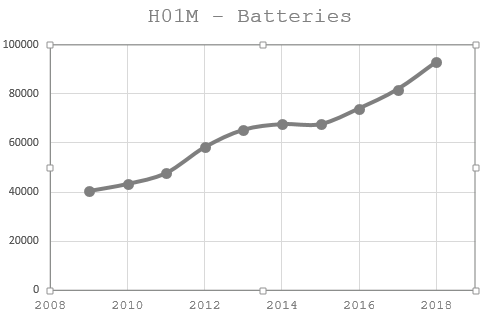

But who is carrying out this R&D? Figure 3. below shows the breakdown of patent publications in 2018.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Asian-based manufacturers are known to dominate the battery market, and the patent publications in 2018 support this view. It is interesting to see that LG Chem had nearly 5,000(!) patent publications last year, which points towards their reported expansion plans over the next 5 years from a capacity of approx. 28 GWh (2018) to 221 GWh (2025). Likewise, Samsung SDI (an affiliate of Samsung Electronics) had over 2,000 patent publications in 2018, also pointing towards their own plans to expand production capacity from 16 GWh (2018) to 132 GWh (2025).

Given the automotive OEMs have concerns that battery production may not meet their needs in the next few years, this expansion is undoubtedly welcome. The battery manufacturers are clearly aggressively building their patent portfolios, and surely with a view to positioning themselves for the negotiations required to supply the automotive OEMs who detest single supplier agreements for any component, let alone such a major component as batteries. The battery manufacturers will need to cooperate – cross-licensing will effectively be obligatory.

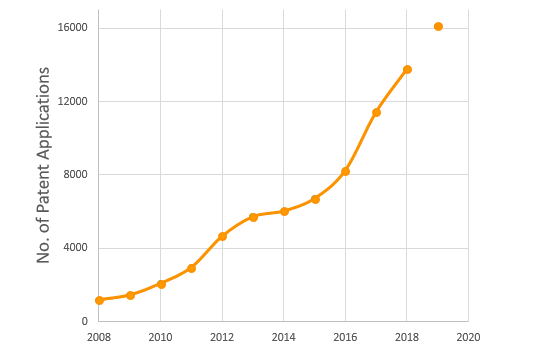

Looking now at Propulsion, and in particular IPC class IPC B60L 11/18 – “Electric propulsion with power supplied within the vehicle” – we see in Figure 4., perhaps as expected, huge year-on-year growth of over 25%.

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

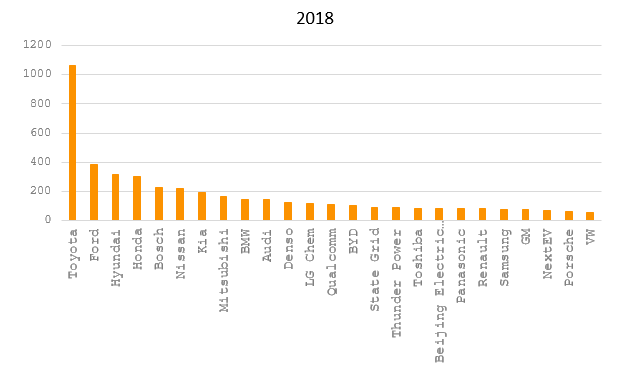

Given the significant, and continued, increases in the number of patent filings in electrified powertrains, our searches looked into the companies that are filing in this area. Figure 5. below shows the publications for 2018, broken down by applicant. The top 10 are perhaps not surprising, and comprise the major automotive OEMs (and Bosch). However, we also see the newcomers, the disruptors, whose technology and entrance into this market may cause concern for the incumbent OEMs.

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

BYD, State Grid Corporation of China, Thunder Power Electric Vehicle, Beijing Electric Vehicle, and NextEV (now known as NIO, Inc.), all Chinese based, and all in the top 20 in 2018. State Grid, the Chinese state owned electricity utility, launched a charging network program in 2010, and are clearly looking to protect their IP in this area, as well as perhaps in technologies such as battery swapping to more closely match the “refill” time of gasoline.

Thunder Power Electric Vehicle and NextEV were both founded in 2014, and have since rapidly developed battery electric vehicles. Along with developing their vehicle models, they have clearly been protecting their IP, and not just in China. These Chinese companies are clearly innovators, and one or more of them will likely present issues for the incumbent OEMs. The technological barriers to entry for electric vehicles are far lower than for more traditional internal combustion engine vehicles, and so given the clear desire for Chinese companies to be innovators and only operate in the electric vehicle market, the incumbent OEMs will likely have to move as fast as they are able to keep up.

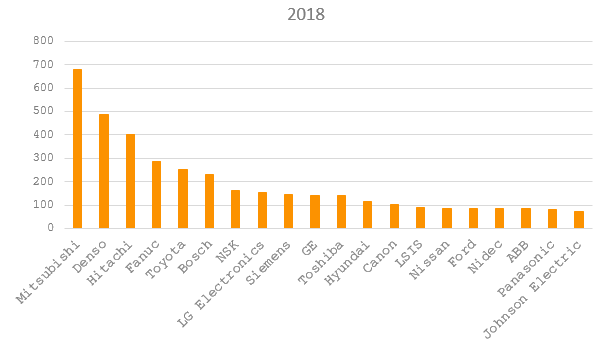

But if we look at Controllers, the patent classification H02P – “Control or Regulation of Electric Motors” – Figure 6., the applicant list is much more akin to what you would expect, some OEMs and some tier 1’s. Given all electric motors in electrified vehicles will require a control system of some form, it seems likely that some sort of more traditional supply arrangement, or perhaps some sort of cross-licensing will be needed.

Figure 6.

Figure 6.

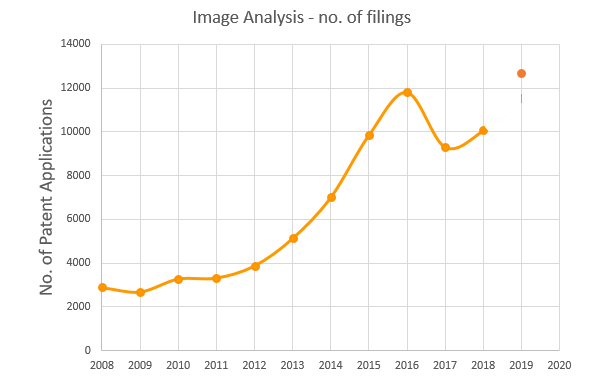

So, on to the “autonomous” part, and starting with Image Analysis + LiDAR, the patent classification G06T 7/00 – “Image analysis” shown in Figure 7. shows year-on-year growth of over 15% over the previous 10 years. Again, growth that is significantly over and above the baseline growth in patent applications generally, and even in patent applications in the broader Transport sector.

Figure 7.

Figure 7.

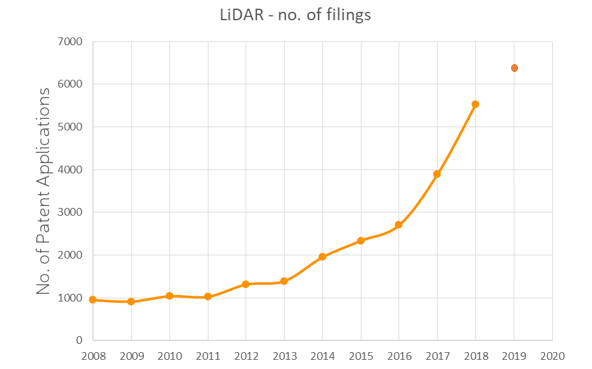

A similar pattern can be seen in patent classification G01S 17 – “LiDAR” shown in Figure 8. where there has been over 20% year-on-year growth for the previous 10 years.

Figure 8.

Figure 8.

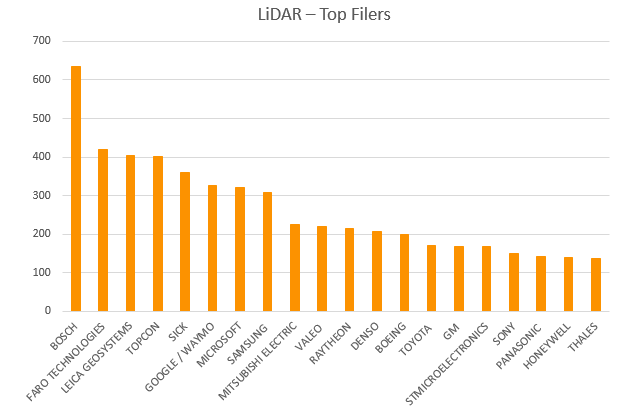

Again, our searches looked into which companies are filing in the area of LiDAR, and this can be seen in Figure 9. below. We see here, in a similar manner to the electric propulsion patent filings, that the top filers include disruptors, innovators, from different sectors moving into this field. However, here those disruptors will more likely collaborate with the automotive OEMs to bring autonomous electric vehicles to market, than compete directly. Here, the technologies required to bring autonomous vehicles to market are far outside the where automotive OEMs are used to operating, and only by collaborating will they be able to bring those vehicles to market in a timely manner.

Figure 9.

Figure 9.

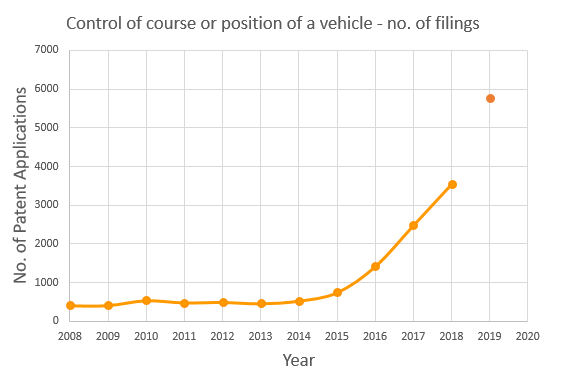

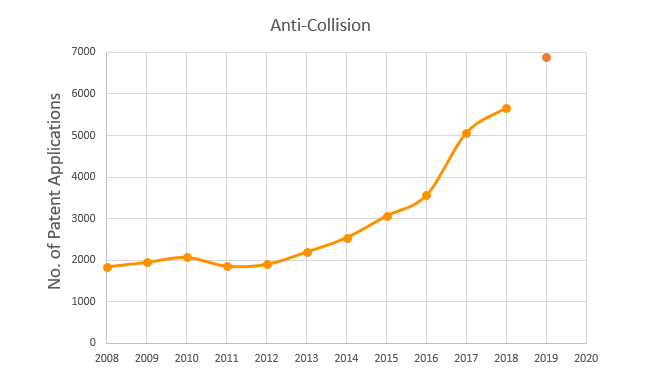

Control of Position, and Collision Avoidance show similar trends, where the number of patent publications have significantly increased in just the previous 5 years or so. These technologies are clearly complementary to image analysis and LiDAR, to first determine the environment of the vehicle, then determine how that vehicle needs to move within that environment to reach its destination, all while avoiding collisions with other vehicles, and its surroundings.

Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Figure 11.

Figure 11.

So, what does the future hold? We see disruptors, innovators, start-ups, entering the market that has been dominated by a few global companies for decades. Those disruptors have significant financial, and in some cases, state, backing and have the opportunity to change the automotive world forever. My personal, and controversial, prediction is for some of the automotive OEMs not to survive the next 10 years of change, at least in the form they are now. However, those incumbents also have an opportunity, an opportunity to collaborate with goliaths from the tech sector to get to market first with autonomous vehicles which may in of themselves completely disrupt the automotive world, with new ownership models, new business models like mobility as a service.

We will have to wait and see whether this particular look into a crystal ball holds any truth, but you can be certain that the next 10 years will see big changes in this sector.

Originally presented at the Future of Transportation World Conference 2019, held in Vienna, Austria.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.