24/02/2020

A recent decision of the General Court demonstrates that the distinctiveness of a trade mark must be assessed in relation to the specific goods or services for which registration is sought.

Hästens Sängar AB (which does business simply as “Hastens”) is a Swedish manufacturer specialising in beds, bedlinen, pillows and accessories.

Hasten’s products have long featured a blue and white check pattern, which was apparently created in 1978 by the father of the current owner and executive chairman of the company. This check pattern is used on Hastens’ beds, mattresses and bed linen, as well as on clothing and other accessories. Hastens has registered the check pattern in Sweden and has sought to protect it by various means in many other territories.

On 21 December 2016 Hastens applied to register a copyright claim in the US in a repeating “two-dimensional graphic pattern consisting of white, dark blue, medium blue and light blue rectangles arranged in a check pattern” – as shown below:

The US Copyright Office refused to register the claim on the basis that there was nothing sufficiently original or creative in the work to support registration. Hastens twice requested reconsideration of the refusal, arguing that a “great deal of thought and creativity” were expended to produce an “optical illusion” of a 3-dimensional cube. However, the Review Board of the US Copyright Office confirmed the refusal.

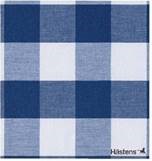

On 16 December 2016, a few days before filing the copyright claim in the US, Hastens had filed International Registration No 1340047 for a very similar trade mark, shown below:

The colours blue and white were claimed.

The International Registration is in respect of the following goods and services:

Class 20: Furniture, including beds, bedsteads and bedroom furniture; mattresses, spring mattresses, overlay mattress; pillows and down pillows.

Class 24: Woven textiles, textile products, not included in other classes; bed linen; down quilts.

Class 25: Clothes; footwear; headgear.

Class 35: Marketing, retail services and commercial information featuring furniture, home furnishing and interior decoration products, textile products, bed linen, bed covers, clothing, footwear and headgear and toys.

The International Registration was based on a granted Swedish registration and it designated multiple territories including the EU. The EUIPO reviewed the EU designation and refused protection in relation to all of the goods and services under Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR, which prohibits registration of a trade mark which is devoid of any distinctive character. The Examiner commented that: “The combination of the presentational features of the pattern does not catch the consumer’s attention and will be perceived merely as a common decorative check pattern, but not as a source of commercial origin or a trade mark.”

Hastens appealed against this refusal, but the Second Board of Appeal dismissed the appeal and maintained the total refusal. The Board of Appeal held that the relevant public, which was found to consist of the general public in the European Union as a whole, would perceive the mark applied for as a simple geometric pattern. The Board of Appeal held that, since such a pattern could be applied to the surface of the applicant’s textiles, furniture and clothing, the mark applied for did not consist of a sign which was unrelated to the appearance of the goods it designated. The Board of Appeal further held that the mark applied for, when applied to the goods at issue, would be perceived as an attractive detail rather than as an indication of its commercial origin, since it did not differ significantly from the norm or customs of the sector. Finally, the Board of Appeal took the view that the mark applied for did not contain any notable variation in relation to the conventional representation of a chequered design found everywhere in the field of textiles.

Hastens applied to the General Court to annul the decision of the Board of Appeal and order the EUIPO to pay the costs. However, the General Court maintained the refusal.

Hastens had argued that the mark did not consist of a pattern covering its goods, but rather a sign which is “not indissociable” from the appearance of the goods and services it covers. This argument was rejected by the General Court. Hastens further argued that the mark was unique and significantly different from the norms of the sector, claiming that no other manufacturer was using similar signs as a logo or label attached to the types of products applied for. Given that the mark applied for was not limited to use as a label or a logo but might be applied to the surface of the products, the General Court dismissed this argument also. Hastens had also submitted that the Board of Appeal had been in error in focussing on the general use of chequered patterns in the textiles sector, arguing that only the perception of consumers is relevant. The General Court also dismissed this argument, stating that the Board of Appeal had rightly assessed the distinctive character of the mark in the light of the relevant public’s perception of it.

The General Court considered that the Board of Appeal was fully entitled to find that the mark applied for was presented in the form of a pattern which could be placed on the surface of the goods in question and was therefore not unrelated to the appearance of the goods. The General Court found that all of the goods applied for could be made from fabric or contain fabric, while the services applied for might concern goods which could be made from or contain fabric. Accordingly, the General Court held that the Board of Appeal had correctly found that the mark applied for consisted of a representation of the possible outward appearance of the goods. The General Court further held that the Board of Appeal was fully entitled to find that the mark applied for did not differ significantly from the norms or customs of the sector, as the chequered pattern is a basic and commonplace style for fabric.

The General Court ordered Hastens to pay costs.

Protection has also been refused in many other territories designated under Hasten’s International Registration, although it has been granted in a few designated territories.

Hasten has also previously tried to register the “check” as a 3D mark. According to the Hasten’s website, this has been done successfully in some countries. However, an EUTM application for the 3D shape mark (below) was withdrawn:

However, Hastens has been able to register its “check” mark in many territories including the UK and EU by including an additional distinctive element or by showing only a portion of the repeating pattern. Examples of such registrations are shown below:

This reflects the differences in approach that IP Offices in different countries may have to issues such as distinctiveness and demonstrates that subtle changes can mean the difference between acceptance and rejection of a trade mark. A Trade Mark Attorney will be able to provide guidance on whether or not a trade mark is likely to be considered distinctive in their own jurisdiction in relation to specific goods and services, and will be able to obtain advice from trusted associates in other jurisdictions where the approach may be quite different.

Case T-658/18

Decision date: 3 December 2019

Judgment of the General Court (Second Chamber)

Composed of E. Coulon, Registrar;: H. Kanninen, President

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.