09/04/2020

In January 2020, the Advocate General (AG) provided his opinion in Santen v INPI relating to how Article 3(d) of the SPC regulation should be interpreted. An AG opinion is not a final judgement but it is a suggestion to the judges of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) on how they should decide a case.

This opinion from the AG is interesting and important for two reasons:

- it is trying to clear up almost 10 years of confusion that was caused by the Neurim judgement; and

- the recommendation provided is very clear.

If the CJEU choose to follow the AG’s guidance then Neurim could be assigned to the history books and Article 3(d) will, once again, mean what is says.

The background

As a quick reminder, Article 3(d) of the SPC regulation states that a certificate shall be issued if: “the authorization [for the product] is the first authorization to place the product on the market as a medicinal product”.

The “medicinal product” and “product” are defined in Article 1 of the regulation and essentially relate to “any substance or composition presented as having curative or preventive properties with regard to human or animal diseases” and “the active ingredient or the composition of active ingredients in a drug” respectively.

It is important to note that this language is more in line with the approach in the US of “one PTE per NCE” and very different from the accepted practice in Japan of getting multiple SPCs on multiple patents relating to the same product/NCE.

Indeed, this narrow, literal, interpretation of the Regulation was the accepted practice in Europe until the Neurim judgement in 2012. Without going into the detail of the Neurim decision it essentially redefined the definition of “product” in Article 3(d) to be:

“a previously authorised product reformulated into a later authorised medicinal product wherein the basic patent does not protect the previously authorised product”.

This positioned Europe somewhere between Japan and the US in allowing more than one SPC on a previously approved active ingredient, but for the last 10 years, the question has been how close to the Japanese approach should the Neurim judgement take Europe?

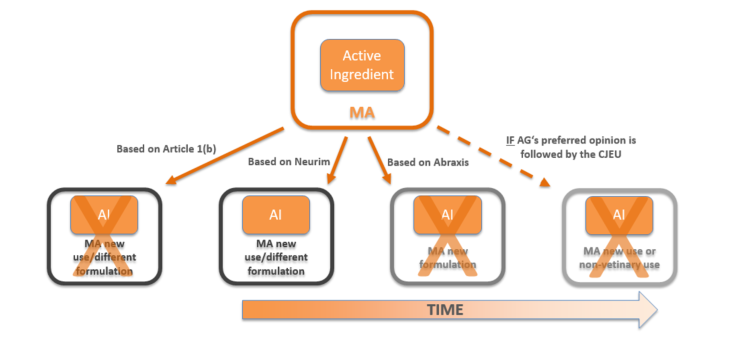

Fig. 1: how the scope of Neurim has been limited over the years and that we may soon be back to an interpretation closer to the literal wording of the Regulation.

In the recent Abraxis judgement, the CJEU decided that the Neurim interpretation should not relate to new formulations of previously authorised products.

This has now been followed by the Advocate General’s opinion in which he goes to great lengths to explain why Neurim is inconsistent with both the Abraxis decision and existing CJEU case law relating to Article 1.

Following this in-depth analysis, the Advocate General gives the CJEU two options:

- either acknowledge that the teleological approach adopted by the Court in Neurim was wrong and should be abandoned; or

- accept the Neurim judgement applies only in cases where the marketing authorization, which serves as basis to the request for a SPC, covers a new therapeutic indication of a previously authorised active ingredient or relates to a use in which the active ingredient exerts a new pharmacological, immunological or metabolic action of its own.

There is no doubt which option the Advocate General prefers. In paragraph 17, he concludes that the interpretation adopted by the Court in Neurim should be abandoned and dedicates the next 46 paragraphs to explaining how he reached this conclusion. In contrast, he dedicates just 10 paragraphs to reluctantly justify the alternative interpretation.

So, if the CJEU do follow the recommendation of the Advocate General, what would that mean for the pharmaceutical industry?

It is fair to say that nobody has been confident in the strength of SPCs based on new indications of old products but following Neurim these were still getting granted, and a granted SPC, with the backing of a CJEU judgement, can be very valuable in preliminary infringement proceedings. Irrespective of their strength they were keeping generics off the market and/or forcing indications to be carved-out.

If the CJEU chooses to abandon Neurim there will be clear guidance that these SPCs should not be granted or are not valid and this could significantly hinder the enforcement strategies of pharma and biotech companies for the next few years. That said, for companies only viewing these SPCs as “upside” when assessing exclusivity for their product, the impact will probably be manageable.

But what about companies whose business model is built around “re-purposing” old medicines?

Developers of personalised medicines; orphan drug developers and companies using big data and AI to identify new, unmet, therapeutic uses are all likely to rely more heavily on this type of SPC to give them valuable additional years of exclusivity. For them, a decision to abandon Neurim could have serious commercial consequences.

At the end of the day, although the Advocate General’s recommendation would undoubtedly bring clarity to Article 3(d) there will still be many who would prefer things to stay as they are.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.