24/06/2020

In a concerted effort to tackle climate change, countries around the world have proposed to ban conventional petrol and diesel cars within the next few decades, paving the way for an electric vehicle revolution.

In our previous blog, The Future Of Automotive Powertrains, we found that in the realm of patents, car manufacturers favour batteries (and lots of them) to power their electric vehicles.

In this blog we look at the capabilities and shortcomings of batteries and how fuel cell technology may yet play a part in powering our transport networks.

The current picture

Petrol-based fuels used by our conventional vehicles have a high energy density and can be stored easily and quickly. These attributes give us the benefits of being able to travel far with few and short stops for refuelling.

Electric vehicles available today largely employ batteries. Most of these batteries are Lithium-ion, which are incredibly efficient (90%), but have a considerably lower energy density than petrol-based fuels (approximately 30 times less). This means that battery-powered electric vehicles need a lot of batteries, and therefore a lot of weight, in order to provide performance comparable to conventional combustion engines. For this reason, in applications where excess weight is undesirable, such as commercial aviation, battery powered vehicles effectively do not exist.

The other well-known drawbacks of battery-powered electric vehicles are a short range and a slow charge-time. However, these issues are becoming less prevalent as the technology improves. Taking Tesla as an example, each of the upcoming Cybertruck and Semi will boast 500 miles of range and the currently available V3 Supercharger can recharge 75 miles of charge in 5 minutes. Moreover, the Chinese car battery-maker CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd) has recently announced a car battery capable of powering a vehicle for 1.2 million miles across a 16 year lifespan. CATL already supply Tesla, as well as other manufacturers such as Daimler, BMW, Toyota, Honda, Volkswagen and Volvo.

These figures, together with the filing statistics in our previous blog, would suggest that for day-to-day road-travel at least, there is little appetite or need for an alternative to battery technology.

Fuel cell electric vehicles

A fuel cell is a device that generates electricity using hydrogen and oxygen. A typical fuel cell includes an anode, a cathode and an electrolyte membrane. Charged hydrogen ions are passed from the anode across the electrolyte membrane to generate current, which can be used to electrically power something. The hydrogen ions recombine with oxygen at the cathode to produce water, the only emission from the process along with hot air. Fuel cells are already used in a wide range of applications, and are particularly useful for providing emergency power in data-banks, airports and hospitals.

Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) are more similar to conventional vehicles in many ways than they are to battery-powered electric vehicles.

Fuel cells do not need recharging, and will instead continue to produce electricity as long as a fuel source (i.e. hydrogen) is provided. The range and refuelling time of a fuel cell is comparable to that for petrol-based vehicles. The fuel cell powered truck Nikola One, for example, has a range of up to 750 miles and a refuelling time as short as 10 minutes.

Furthermore, the energy density of fuel cells is much higher than that of batteries. This means that, in theory, fuel cells can store much more energy for the same weight when compared to batteries. For this reason, in applications where the disadvantages of batteries are laid bare, such as longer distance road-travel, aviation and shipping, interest in fuel-cells remains prevalent.

In practice, fuel cells require associated tanks, pumps and a means of keeping the system cool. This parasitic weight has historically been somewhat of a barrier to fuel cells being used in certain applications such as aviation.

However, advancements are being made in this area. HyPoint, a new company based in California, has demonstrated an air-cooled hydrogen fuel cell powertrain that produces 1000 W/kg of specific power with an energy density of 530 Wh/kg. It is hoped that devices such as these could be used to power eVTOLs and small aircraft. Hypoint’s next powertrain will supposedly reach 2,000 W/kg specific power and 960 Wh/kg energy density. These figures far exceed the energy density attainable by lithium-ion batteries with a comparable power output.

Patent Perspective

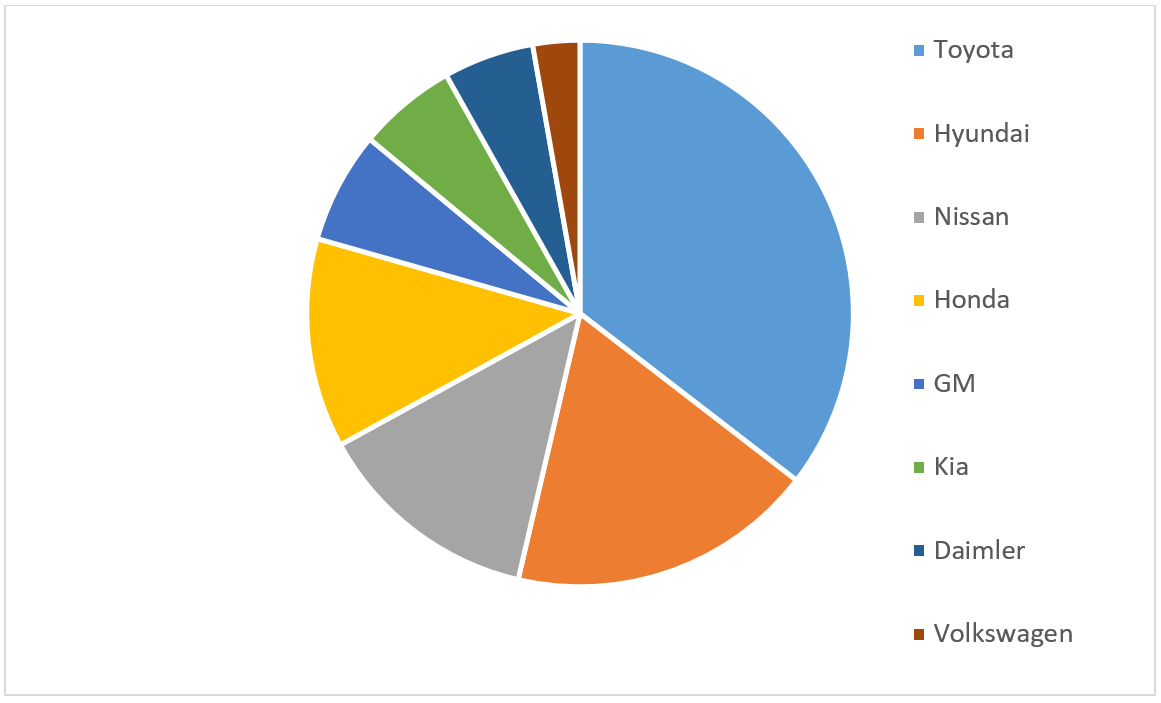

Patent filing and publication statistics are often a good indicator of the technologies particular industries and companies are focusing on. Although filing numbers relating to fuel cells are dwarfed by those for batteries the general trend is upwards. In terms of the companies that have been innovating in fuel cells in recent years, it is interesting to note that the companies with the biggest fuel-cell related portfolios are all car manufactures, as shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Top 8 Assignees, Fuel Cell related patents (CPC: H01M2250/20)

Regardless of the progress of batteries, cars are still the biggest market for fuel cell technology. Of the top eight companies shown above, there is a notable focus on the Far-East. Three are Japanese (Toyota, Nissan, Honda), and the biggest fuel cell advocate, at least in patent terms, is Toyota, with 36% of the total number of filings of the top eight companies. South Korea has two applicants in the top eight (Hyundai and Kia).

The governments of Japan and South Korea are both actively encouraging growth and production of FCEVs. Japan wants to have 800,000 FCVs on the road by 2030 and South Korea wants 850,000. In September of 2019, the ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) of Japan set out a strategy for reducing Japan’s reliance on imported energy, reducing Japan’s environmental footprint, and positioning Japan as a fuel cell technology exporter. This comes after Japan has and continues to provide subsidies for the research and manufacture of FCEVs.

Future outlook

It would appear that, thanks in large part to companies in Japan and South Korea, FCEVs still have some part to play in the future of road transport. It will be interesting to see exactly how big and wide-spread this part is. Whilst Japan and South Korea may yet achieve their targets relating to FCEVs, the roll-out of these vehicles may only be local. If other parts of the world do not share the ambition of the Far East, and opt to stick with batteries, it will be difficult to attract the large investments needed for the necessary FCEV related infrastructure (refuelling stations, mass hydrogen production) to make FCEVs feasible. That being said, it seems there will be niches, in long distance travel, or aviation, where FCEVs may gain some better footing due to the advantages fuel cells have over heavy batteries.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.