28/10/2020

Increasing focus is being directed to developing Li-ion battery technology, particularly in view of the expected surge in uptake of electric vehicles (EVs) in the near to short term. It is not hard to imagine a future where battery powered EVs have replaced many, if not all, of the internal combustion engines on our roads. However, a number of concerns arise when looking towards this battery powered future, and highlight the need for robust recycling practices and technologies.

Firstly, some speculate that the supply of the raw materials, especially lithium, nickel and cobalt, required to produce future batteries could struggle to meet demand. Although it is unclear whether these concerns are well-founded, developing methods to recycle and extract the raw materials from spent batteries would alleviate any potential future pressure on supply chains.[1]

Mining for the raw materials used in batteries is also associated with significant greenhouse gas emissions, and is often linked to significant environmental damage and unethical practices in some countries. Recycling batteries to recover and reuse already mined raw materials, would help reduce the need to mine for “fresh” raw materials.

Lastly, recycling the mountain of used batteries likely to be produced by a future fleet of EVs, as well as from other electronic devices, is desirable to prevent millions of tonnes of hazardous materials contained in the batteries ending up in landfill. At present less than 5% of Li-ion batteries are currently recycled.[2]

Why is recycling not currently prevalent?

There are many factors that have formed barriers to widespread recycling of Li-ion batteries. These factors include technical hurdles, future uncertainty, and economic viability. First, Li-ion batteries are complex integrally formed objects, with a large number of different materials assembled in such a way that prevents simple separation of the components. Therefore innovative solutions to facilitate deconstruction and recycling of these batteries are needed, and this requires time and investment.

Second, there is uncertainty as to whether Li-ion batteries will be in use in the long term, or whether new technology, for example solid state batteries (discussed in our previous blog here) or even hydrogen fuel cells, could eventually replace Li-ion batteries altogether, and discourage investment in Li-ion recycling technology.

Lastly, the raw materials required for manufacturing Li-ion cells are presently in good supply and available cheaply. In contrast the supply of spent batteries is not yet at high enough levels to make recycling commercially viable. It’s currently easier and cheaper just to mine for new materials.

Innovation so far: filings per year

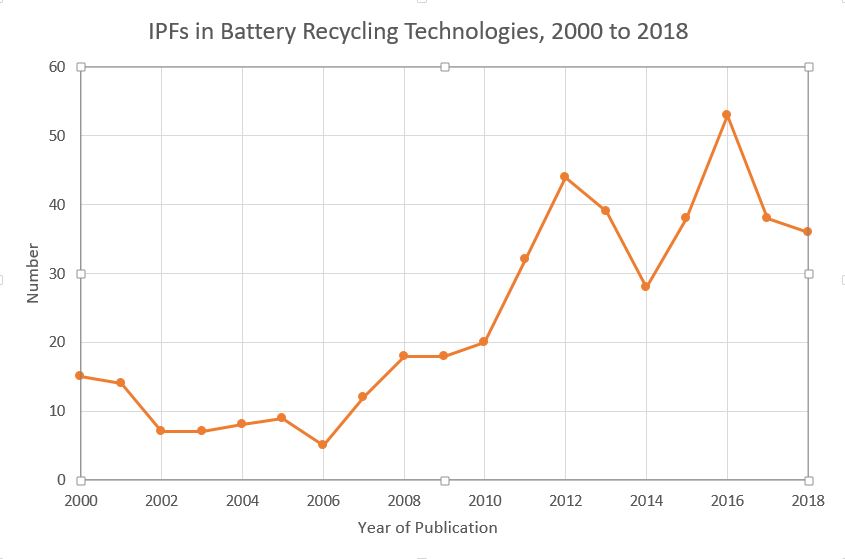

A recent report by the EPO on innovation in batteries and electricity storage, discussed previously here, touched on the topic of recycling batteries, and included data for the number of published international patent families (IPFs) relating to battery recycling in the last 20 years. The report defines IPFs as any patent family containing applications in more than one jurisdiction, and states this is:

“a reliable proxy for inventive activity because it provides a degree of control for patent quality by only representing inventions for which the inventor considers the value sufficient to seek protection internationally.”

The EPO data includes IPFs from at least one of three IPC classifications:

H01M10/54 Secondary cells; Manufacture thereof: Reclaiming serviceable parts of waste accumulators.

H01M6/52 Primary cells; Manufacture thereof: Reclaiming serviceable parts of waste cells or batteries.

Y02W30/84 Technologies for solid waste management: Recycling of batteries or fuel cells.

The data, reproduced in Figure 1 below, unsurprisingly showed an increasing trend in IPFs in these classifications in recent years, and a doubling over the past decade. However, the overall number of IPFs for battery recycling remains relatively low, at 436 in total between 2000 and 2018. It appears substantial research and investment is therefore required in developing this technology if recycling rates are to be increased in time.

Figure 1: Number of IPFs published in battery recycling technologies between 2000 and 2018.[3]

Innovation so far: filings per country

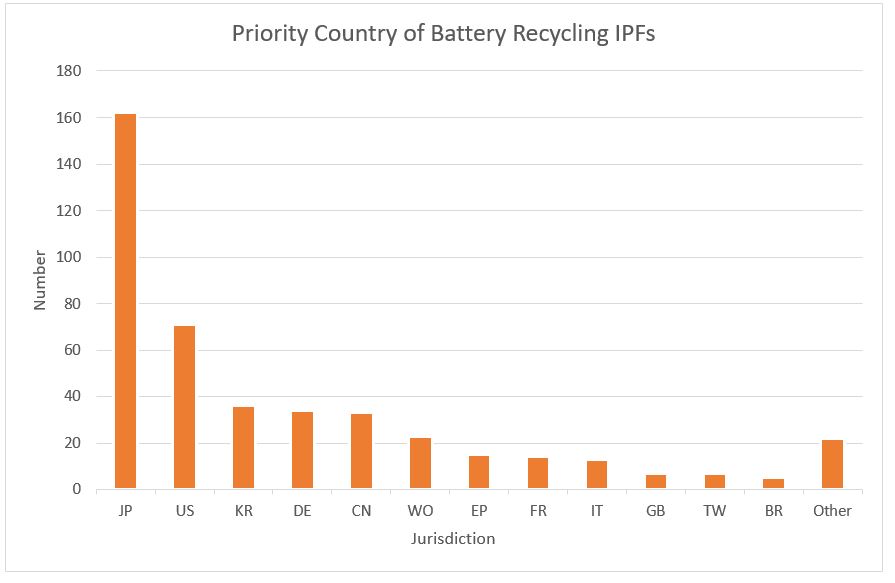

To delve further into this data, we replicated the EPO’s results using a TotalPatent search of the three classifications above. Applications for one jurisdiction, and therefore not counting as IPFs under the EPO’s definition, were removed. There were over 3000 applications filed in a single jurisdiction only, and therefore not qualifying as IPFs, compared to the 400 or so applications filed more widely. The majority of the single jurisdiction families were Chinese applications, the large number likely being the result of state incentives to file applications coupled with China’s shift into greater levels of industrial and technical innovation. The fact that these applications were not continued with overseas is either testimony to the powerful but distorting power of state incentives, or to the fact that competitors were based locally.

Figure 2 shows a breakdown of the country of the priority application for the IPFs. Although not an exact indication of the nationality of the patentee or the country in which the innovation occurred, it can be a useful proxy. Perhaps unsurprisingly Japan dominates as the main priority country, with almost 40% of the IPFs having a Japanese priority document. The US is the second most common priority jurisdiction, with Korea, Germany and China being evenly matched to round out the top five.

Figure 2: Number of IPFs published per priority country in battery recycling technologies between 2000 and 2018.

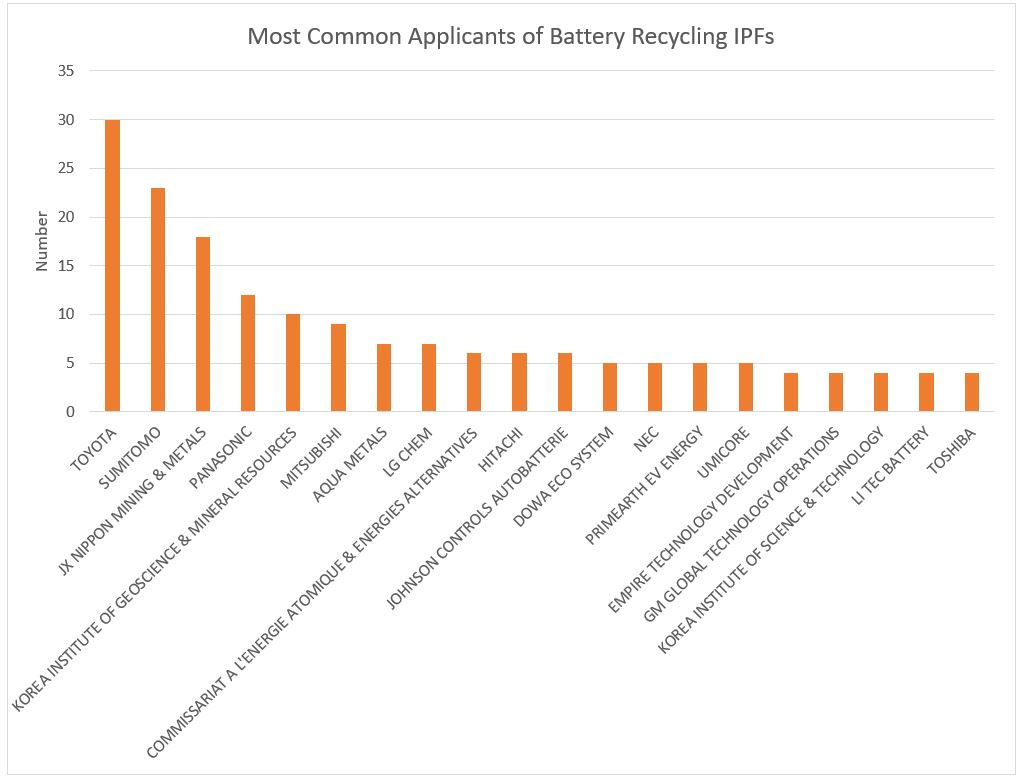

Innovation so far: filings per applicant

We also looked at which companies filed the most IPFs in these battery recycling classification codes. The results are shown in Figure 3 below. Asian companies dominate these standings, with Japanese companies taking most of the top spots. This is not surprising given Japanese industry’s historic strong standing in the battery, energy, and automotive sectors.

Figure 3: Number of IPFs published in battery recycling technologies by the top 20 most frequent applicants between 2000 and 2018.

Key Technologies

The EPO report (see above) discusses a number of the key Li-ion recycling technologies used today, in which at least some of the IPFs holders above are engaged, and our previous report, available here, discussed some of the other technologies featured.

One notable technology is smelting (pyrometallurgy), which can extract elements including cobalt and nickel, and Umicore in particular has provided recycling services based on this technology since 2006. However, lithium and non-metallic elements cannot be extracted via pyrometallurgy, meaning that an effective recycling solution is not yet possible.[4,5]

Chemical leaching (hydrometallurgy) is another method for extracting materials from the spent batteries. Although this method allows lithium to be successfully extracted, it often relies on the use of harmful chemicals. At present, recycling via pyrometallurgy and hydrometallurgy can sometimes produce more greenhouse gasses than simply using freshly mined resources.[3]

The Future

It is clear therefore that more development is required to create a viable recycling system for Li-ion batteries that can recycle all of the materials in a Li-ion battery and form a closed loop system. Encouragingly, this development does appear to be happening.

A number of start-ups have entered the market in this sector, promising cleaner and economically viable recycling. In particular, Duesenfeld and Li-Cycle have both developed new recycling methods combining mechanical separation and hydrometallurgical methods.[6,7] Both of these start-ups appeared on the list of applicants for the IPFs discussed above. Northvolt is another recycling company that has attracted significant investment recently. Many other novel ideas are also being explored, such as biological recycling, which involves using biochemical processes in bacteria to break down and separate the materials inside Li-ion batteries.[8] As well as developing new recycling technology, redesigning the batteries themselves so that they can be recycled easier would be a useful tool to prevent waste. Tighter government regulations would also help, with China already leading the way in this area by forcing EV manufacturers to collect spent Li-ion batteries.[6]

Lastly, the idea of “second life” is also likely to become important in preventing waste batteries. Typically a 20 to 30% reduction in capacity would spell the end for an EV battery. However, even with this reduced capacity, the EV battery could still be more than sufficient for other non-automotive applications. Repurposing batteries for second life applications can prevent, or at least delay, the need for recycling in the first place.[3] A quick TotalPatent search revealed only 3 of the above IPFs included the term “second life”, suggesting there is much more room for the development of IP in this area.

Based on the amount of research and development that appears to be ongoing, we are cautiously optimistic that a viable recycling system can be reached. As to whether innovation in recycling can keep up with the uptake of Li-ion batteries, or whether Li-ion batteries will themselves be superseded by newer technology, only time will tell.

At Reddie and Grose we have a wealth of experience in the clean tech and electrical engineering sectors, including battery technology. If you would like help protecting your innovations in these fields then please get in touch.

This article is for general information only. Its content is not a statement of the law on any subject and does not constitute advice. Please contact Reddie & Grose LLP for advice before taking any action in reliance on it.